In 1933, the nation’s real estate professionals eagerly anticipated their annual convention in Chicago.

After several sedate, unadventurous conferences focused on surviving the Depression economy, the 1933 meeting promised to be special: The Century of Progress International Exhibition, better known as the Chicago World’s Fair, happened to be taking place at the same time. “Come to the REALTORS®’ best convention,” read promotional material mailed to each member. “Come to the World’s Fair!”

A day was set aside in the convention schedule to allow attendees to explore the fair. Of particular interest to the convention attendees was the fair’s Home and Industrial Arts section, which featured 11 model houses showcasing the latest building methods and technologies. “Full-size houses, completely finished and equipped, have been erected in the Housing Division at the World’s Fair,” declared another promotional mailing. “REALTORS® will be interested in studying these exhibits because they present the newest architectural trends and show many new materials, processes, and inventions.”

Earlier this year, the Elmhurst Art Museum in Elmhurst, Ill., offered a chance to revisit one of the 11 houses featured at the 1933 World’s Fair, the groundbreaking House of Tomorrow. “Houses of Tomorrow: Solar Homes from Keck to Today” told the story of how the House of Tomorrow’s use of passive solar energy and other innovative features launched the exponential interest in sustainable energy-efficient homes that we’re experiencing today.

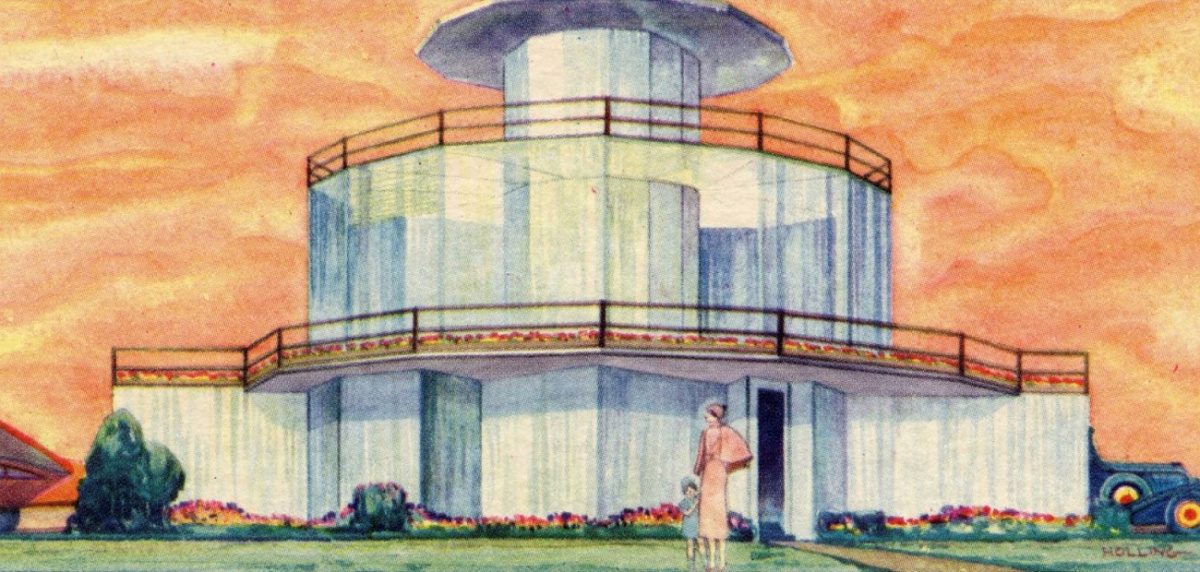

The House of Tomorrow was designed by Chicago architect George Fred Keck, a contemporary of Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson. His twelve-sided house was easily the most experimental of the Century of Progress homes and is recognized as being the first glass house built in the United States, preceding those designed by Johnson and van der Rohe by more than 15 years.

Irvin Blietz, a REALTOR® from Chicago and one of the organizers of the Home and Industrial Arts exhibit at the World’s Fair, gave a full description of the house in his presentation during the 1933 REALTORS® Convention:

“The House of Tomorrow is striking in design. It has a steel frame with a round steel tower as its center structural support. All the utilities of the house are carried in this round tower. The main staircase of the house winds around this tower. The house is entirely enclosed in plate glass. Venetian blinds with a coating of aluminum are used for a dual purpose – first, so that people in glass houses can take a bath, and second, as a deflector of heat and cold. It has been discovered that aluminum, because of its deflecting power, is a splendid insulator. Aluminum foil no thicker than paper is used as an insulator between the roof and the coiling. Wood floors are in place but are not nailed to the subfloor—instead, they are held in place by a grooved and locking device. […] The architect claims the houses we will live in tomorrow will have to have hangars and planes, so this house has a hangar and airplane. Air conditioning is part of this house.”

In addition to its credentials as the first glass house and the first to use passive solar energy, the Elmhurst Art Museum exhibit listed several other design innovations and features that made their debut in the House of Tomorrow. They include:

- An open floorplan

- An electric garage door opener (an invention that wouldn’t become widely available until after World War II)

- The first General Electric dishwasher and a new “iceless” refrigerator

- An “electric eye” that projected images from the home’s exterior onto a screen inside (a precursor to today’s smart doorbells)

- The first domestic use of motion sensors to automatically open and close the kitchen door

The House of Tomorrow, as Blietz explained in his presentation, was intended to be a laboratory of sorts, built to show fair visitors a uniquely different kind of home with amenities that they might encounter sometime in the future. Other homes in the exhibit were more practical and less costly, highlighting new technologies that could potentially revolutionize homebuilding right away. Steel-frame construction methods and manufactured stone exteriors caught the attention of the real estate professionals, along with the latest kitchen design trends that they could pass along to their clients back home.

After seeing how people interacted with and reacted to the House of Tomorrow, George Keck and his brother William continued to develop the ideas that went into its visionary design, according to the Elmhurst Art Museum exhibition. Rather than focusing on all-glass structures as a design element like other architects, the Keck brothers expanded on the engineering potential of glass, pioneering techniques that would better allow for passive solar heat to keep a structure warm or cool it as conditions required. They went on to design and build hundreds of houses throughout the Midwest, including a series of prefabricated solar homes, which are still much desired by buyers for their large window walls and energy-saving features.

After the World’s Fair closed in 1934, the House of Tomorrow was sold to a private owner and relocated to land that is now part of the Indiana Dunes National Park. It is currently owned by the National Park Service and is awaiting a restoration plan.