Real estate investing has always been haunted by charlatans and scandals. Timeshare condominiums, swampland (ummm … critical wetlands) in Florida, bridges near Manhattan … heck, the whole reason that Greenland is called “Greenland” and not “utterly f’ing desolate wasteland covered with 1000 carnivores who scare even grizzlies land” was a real estate marketing scam.

The cold coast of Greenland is barren and bare,

No seed-time nor harvest is ever known there.

And the birds here sing sweetly in mountain and dale

But there’s no bird in Greenland to sing to the whale.

There is no habitation for a man to live there

And the king of that country is the fierce Greenland bear.

“Farewell to Tarwathie,” ca 1850

At the same time, Americans and their English forebears are especially passionate are owning their own little patch of ground. Fewer of us think about real estate as a part of our investment portfolios; we consign that sort of thing to the Trumps of the world. (Though the former president no longer makes The Forbes 400 List, two dozen others on the list are there by dint of their real estate holdings.)

While 60 million investors own REITs directly or through their funds, they represent a fairly small slice of the average portfolio and are still held by a minority of investors. Morningstar, which is pretty dispassionate about such things, concluded that a well-diversified portfolio would gain from a 13% allocation to real estate. That was news to me.

Normally I write about subjects I’m familiar with. This is a little different. It’s a piece about real estate funds, a sector I don’t have much experience with. But some people here have raised questions about the sector. So it seemed like a good opportunity to gain some knowledge on the subject and pass along what I find.

We’ll see how well I simultaneously read about a less familiar subject and write about it. I even throw in a little ‘rithmetic. For the most part what follows is fairly basic. It considers what it means to invest in real estate (and funds in particular), what makes the sector attractive, and how the investments work. It concludes with a list of representative funds and what makes them interesting.

Types of real estate investments

What is real estate and what does it mean to invest in real estate? Black’s Law Dictionary defines real estate as “Land and anything permanently affixed to the land, such as buildings, fences, and those things attached to buildings such as light fixtures, plumbing, and heating fixtures …” That comports pretty well with one’s common sense.

At first blush, investing in real estate suggests investing in buildings that one can operate and rent out to tenants. Apartment buildings, office space, shopping malls, lodging (hotels/motels), maybe even individual houses. More specialized or “modern” types of buildings that can be rented out include infrastructure (cell towers, etc.), data centers, self-storage facilities, and healthcare space.

Going in the opposite direction, rather than “improving” the land with specialized buildings, one could acquire and rent unimproved land to farmers. Or one could rent out land, trees, and facilities for lumber production.

The common theme is that all these types of land-associated properties are rented out by the owners/investors and generate income streams. If the property isn’t somehow associated with land, then buying it isn’t considered a real estate investment. So car rental companies don’t count.

REITs for income, REOCs for growth

Oh my!

One may invest for income, for growth (appreciation), or for both. The types of real estate investments presented above are income oriented. One owns these properties primarily for the income they generate. This is similar to investing in “equity income” funds, where one owns companies for the profits they distribute as dividends.

A Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) is a legal structure created to invest in real estate for income. Like a mutual fund, it passes its earnings through to its owners in the form of dividends. So it doesn’t pay taxes itself. And because it doesn’t retain its earnings, it can’t easily plow those earnings back into more properties.

A different form of real estate ownership, the Real Estate Operating Company (REOC) is oriented more toward growth. It isn’t required to pass earnings through to its investors. But someone is still responsible for the taxes on those earnings. It is the REOC that pays the tax bill.

What all of this has to do with real estate mutual funds is that mutual funds are generally limited to owning securities, not land. They can invest in real estate only indirectly. So they invest in REITs, REOCs and other forms of land ownership that are considered securities.

Looking at the portfolio composition of Vanguard Real Estate Index Fund (VGSLX / VNQ) we get a good sense of just how much of the real estate market is wrapped up in REITs. The various REIT sectors in the fund add up to 95.5% of the portfolio. While it is not entirely accurate to call real estate mutual funds “REIT funds”, for all practical purposes, most are.

Reasons to invest (or not) in real estate

Returns, diversification, inflation protection, and income are often given as reasons to invest in the sector. Typical arguments against investing in real estate are that you already have a large real estate investment if you own a home and also that the sector is more volatile than equities. All of these considerations can be scrutinized. There’s some truth in them, but they are not as one-sided as they seem.

Real estate contribution to a portfolio – returns, diversification, volatility

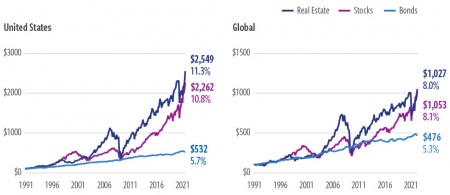

Depending on the time frame analyzed, real estate has returned a bit more, a bit less, or about the same amount as the stock market. The graphs below show performance between 1991 and 2021. They come from Cohen and Steers, a granddaddy of real estate mutual funds. Its first fund, Realty Shares (CSRSX), started in 1991.

Over these 30 years, domestic real estate modestly outperformed stocks, while globally real estate ever so slightly underperformed stocks. Had the time frame selected been 15 years (2006 – 2021) instead, real estate would have fared worse than stocks. One can see a large real estate peak in 2006, after which it fell much more sharply than stocks. It is not unreasonable to say that real estate and stocks have performed similarly, though by following different paths, over the long term.

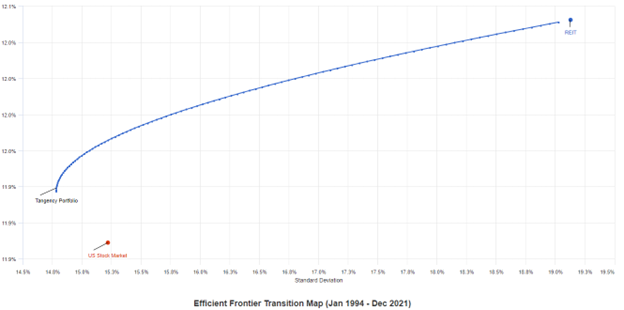

Real estate has been more volatile than stocks over the long term. Portfolio Visualizer reports that between 1994 and 2021, REITs had a standard deviation of 19.13%, while the standard deviation of the US stock market was significantly lower, at 15.22%. Meanwhile, the returns of each asset class were close together: 12.07% for REITs vs. 11.91% for stocks.

Despite the volatility of real estate being higher than that of stocks, adding real estate to a pure stock portfolio can reduce its volatility while increasing expected returns. This magic happens because the correlation between the two asset classes over the same time period was just 60%. Portfolio Visualizer shows the potential efficient frontier map, and reports that a roughly 75/25 stock to REIT mix would give the highest Sharpe ratio.

Such analyses can only go so far. Portfolio Visualizer reports that the optimal (maximum Sharpe ratio) blend of US stocks, US bonds, and REITS over the same period is 84% bonds, with the rest being stocks. That’s not a portfolio typically suggested for anyone including retirees.

Income and inflation protection

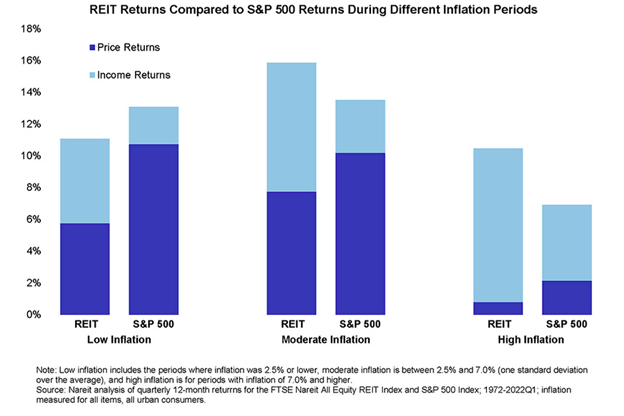

Real assets provide substantial inflation protection due to intrinsic value independent of money supply. Further, when it comes to land, they aren’t making more of it. So disregarding short term fluctuations, real estate should hold its value if not appreciate in real terms.

That expectation is borne out by a comparison of equity and REIT returns over the 50 years between 1972-2022.

Source: REIT.com

But wait, there’s more than just price gains. Unlike an investment such as gold, land actually generates income. You get rent from it. In this sense, real estate resembles businesses. This is why Warren Buffett grouped it together with businesses and farms as productive assets in his 2011 annual letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders.

That rental income results in a relatively high dividend rate for REITs and the mutual funds that invest in them. To the extent that the dividends represent rent, they are taxed as ordinary income. But there are a couple of tax quirks that reduce this impact. The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act introduced a 20% tax deduction for dividends of REITs and of funds that invest in them. That ends (sunsets) after 2025. REITs are also able to depreciate their investment property. On paper, that reduces their taxable income. So some of part of the dividends may be characterized as nontaxable return of capital.

For those looking for even more income, there’s something called a mortgage REIT (mREIT). Instead of investing in real estate, they invest in mortgage-backed securities. Since these are related to ownership of real estate, they’re still considered real estate investments. And since these are actually bond investments, usually leveraged, they tend to have even higher yields than equity REITs. These mREITs are used more often in real estate mutual funds focused specifically on income.

Source: REIT.com

Owning a home

Is a home an investment? What Cohen and Steers writes:

A house is generally considered a consumption item, not an investment. Rather than generating income, a primary residence consumes it in the form of mortgage interest, real estate taxes, insurance payments, utility expenses and the costs of repairs and maintenance. In contrast, REITS generate rental income from real estate such as commercial, industrial and multi-family residential, which is then distributed to shareholders via tax-advantaged dividends.

That’s one take. My view is aligned with the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In calculating the inflation component of housing, it deconstructs real estate into an investment component and a shelter component.

If you buy a house, rent it out for $3K/month that’s an investment. But you have to live somewhere, so you rent an identical house and pay the same $3K/month to live in it. That is equivalent to living in your own house and paying yourself that $3K rent. It sounds silly, but economically there’s no difference. Either way your cost of “consuming” shelter is $3K and your house is an investment asset that brings in rent (sort of) and should appreciate over time.

On the other hand, your house is much less liquid than a REIT or a real estate mutual fund. And you could be forced into a fire sale if your job relocates and the market is swooning. There are ways to mitigate these effects, but with costs and effort.

So, owning your home does give you some exposure to the real estate market, but it isn’t the same as a pure real estate investment. Home ownership is just another factor to consider when investing in real estate.

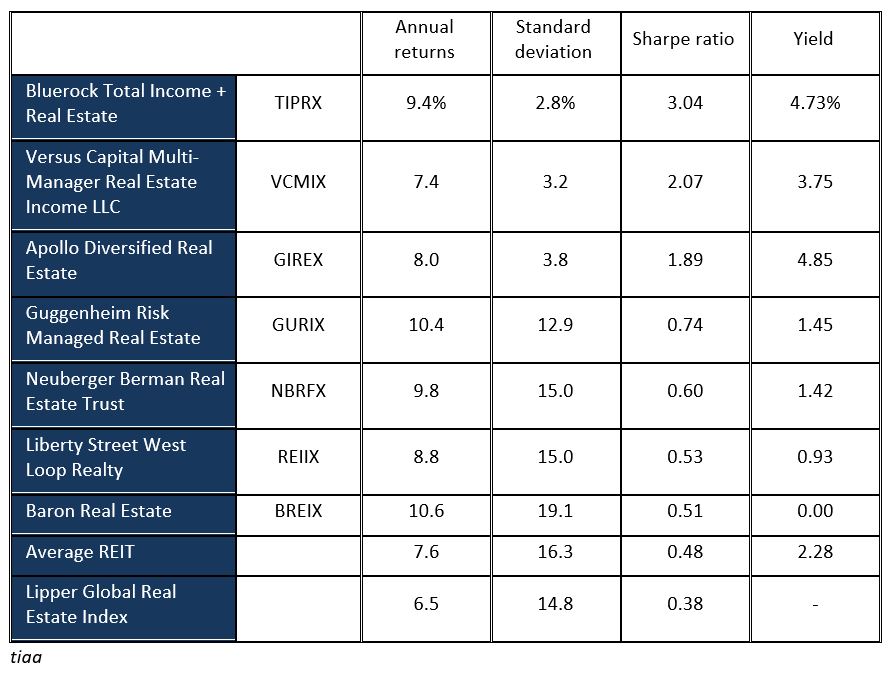

A few funds to consider

The funds below are mostly the usual suspects. They are accompanied by brief descriptions of why these particular funds are included here.

- Index funds

Vanguard Real Estate Index (VGSLX / VNQ) – the elephant in the room, about nine times as large as the next largest fund (excluding TIAA, below). Broadly diversified in subsectors and in quantity (160+), middle of the pack, high trailing yield (2.9%).

State Street Real Estate Select Sector SPDR (XLRE) – broad subsector diversification while concentrated (30+ holdings), excellent performance (MFO Great Owl, Morningstar 5 star fund), high trailing yield (2.7%).

- Actively managed funds

Cohen and Steers Realty Shares (CSJAX / CSJIX) – Cohen and Steers is the actively managed fund family elephant, running this and similar sibling funds, ETFs, and other real estate vehicles. This retail fund is still open to new investors and dates back to 1991, so it is useful as a benchmark. Because it and its siblings are actively managed, its large size and concentrated portfolio (30+ holdings) is a concern. Nevertheless, the fund and the firm have stood the test of time. The fund is currently rated 4 or 5 star by Morningstar depending on share class. Trailing yield is a respectable 1.6%-1.8%.

TIAA-CREF Real Estate Securities (TCREX / TIREX) – a pretty standard fund with low expenses (ER), fair trailing returns (1.2% – 1.4%) and a solid 5 star performance.

TIAA Real Estate Account (QREARX) – a unique investment. It is not a mutual fund, but an account that is available within some TIAA annuities. Unlike mutual funds, it owns real estate directly. In a sense it is itself a giant REIT, one that invests only in “traditional” real estate – offices, apartments, retail, etc.

This apparently gives it a distinctive performance profile. The account operates as an almost pure diversifier, with a ten-year negative correlation to the stock market. TIAA reports:

Returns are largely unaffected by movements in stock or bond markets since returns are generated by rental income and changes in property values. For the 10-year period ended September 30, 2021, REA correlation to the S&P 500 Index and Barclay’s Aggregate Bond Index was -0.03 and -0.09, respectively. Over this same period, correlation between the FTSE Nareit All Equity REIT Index and the S&P 500 Index was 0.71.

The account has returned 6-9% annually over periods between three and 30 years. While 6.58% – its annualized return since inception – doesn’t seem like much to write home about, its independence of the stock market means that it may be your sole stalwart when other assets falter. By way of illustration, it has returned 9.68% YTD as of Memorial Day, 2022. In comparison, the best YTD performance of open- end real estate funds on Morningstar’s site is -5.91%. That may explain my colleague David Snowball’s decision to devote 20% of the TIAA-CREF slice of his retirement account to the real estate account, though he warns that it suffered a bloody fate in the 2008 real estate market implosion.

Our colleague Devesh Shah released a great investing video series on real estate, with the second half of this video focused on the TIAA account. Devesh notes that it can be purchased directly from TIAA.

If you have a 403(b) with TIAA, you probably have access to this fund. If you are in the same family as someone with a TIAA 403(b) you can open an IRA with access to the same accounts including this Real Estate Account.

- Income oriented real estate funds

Fidelity Real Estate Income (FRIFX) – a usual suspect, included as an example of a fund that may invest a substantial portion of its portfolio outside of equity REITs. It currently holds about half its assets in fixed income, largely commercial mortgage-backed securities. And yet its trailing 1.4% yield is not enough to stand out.

iShares Mortgage Real Estate Capped ETF (REM) – a pure play in mortgage REITs. Higher yield (7%) than equity oriented real estate funds, and a lower total return.

- Fund with significant REOC and other real estate management holdings

Baron Real Estate (BREFX) – the focus is on growth, not on income. This is reflected in its trailing yield – a perfect 0%. Excellent long term growth: an MFO Owl, a Morningstar 5 star rating. A high octane fund, atypical of real estate funds.

For readers looking for the Great Owls in the bunch, here are the six funds (and two benchmarks) that earned Great Owl status from 2015-2022.

Conclusion

In limited doses, real estate funds have the potential to temper a portfolio’s volatility and generate a fair amount of dividends. The vanilla (equity REIT focused) funds are likely to best serve this purpose. Alternatives exist if one is more focused on income or if one is more interested in real estate-related growth.