The word infrastructure derives from the French “infra” meaning below or beneath, and “structure” meaning something constructed. Infrastructure is the physical assets that form the foundation of an economy. Society benefits from good infrastructure and the quality of infrastructure is often a key determinant of economic development.

Globally, the creation and operation of infrastructure are primarily the domain of government, with the World Bank estimating that 83% of global infrastructure funding derives from public sources. When the authorities do not own or operate infrastructure assets, they tend to regulate them heavily.

Private participation

Private interests have been involved in infrastructure since Roman times when citizens bid for the right to operate and maintain a postal station and surrounding roads for five years. Today, private companies can and do build their own infrastructure (such as an oil company laying pipelines) or are invited by public entities to participate in the funding, design, construction and/or operation of infrastructure. The private sector can often be more efficient and provide expertise and/or funding lacking in government. Done correctly, the whole of society stands to benefit.

At Coronation, some of our portfolios have exposure to various businesses operating within the infrastructure sector.

The key attraction for investors in infrastructure assets is their extremely stable, defensive cash flow streams that benefit from inflation and economic growth.

While a precise definition for infrastructure is difficult to pin down, the businesses in which we have invested have the following in common:

- They are physical assets with a foundational role that is demonstrated by their widespread use by consumers and enterprises.

- They are capital intensive to build, but normally relatively low cost to operate and maintain.

- They benefit from economies of scale, as largely fixed-cost bases are spread over more units.

- Unlike most businesses, they generally have limited competition in the locations in which they operate. They have local monopolies that are likely to endure – it is normally either impossible, or too expensive and time consuming to replicate.

- They operate within a (often very strict) regulatory framework to prevent them exploiting their market position.

Regulation is key

Regulatory frameworks differ across assets and countries, but in many cases can provide high visibility of earnings to investors. Regulatory environments range from fully regulated on either prices or returns to fully deregulated. Each framework has its pros and cons. A utility company is regulated on a certain return – but has very little risk of earning less than this; while price regulation provides great certainty of revenue and cash flows it requires tight cost control. On the other hand and largely as a result of history and a free market economy, North American rail companies are practically totally deregulated and free to set their own prices. This has been beneficial to both companies and users.

As an illustration of the attractions of infrastructure investment, we will discuss two examples on either end of the regulatory spectrum.

Regulated operators: VINCI (listed on Euronext Paris)

- Owns attractive regulated toll road and airport concessions

- Highly visible and certain cash flows from toll roads

- Will benefit from travel recovery

- Construction division will drive future participation in new public-private partnerships

Headquartered in France with a global footprint of 120 countries, infrastructure giant VINCI traces its roots back to French construction companies that have been operating since the 19th century. Construction companies build the infrastructure that society requires but are normally poor businesses with very thin margins. Years of accumulated profits can be wiped out by a single large problem contract. Running a successful contracting company is mostly about managing and pricing risk; and as evidenced by their longevity, VINCI has an excellent track record in this regard. In the past 20 years, they have not had a single year of negative earnings in contracting (including through the pandemic).

Concessions of public infrastructure have long been a part of their activities and started with water and sewage networks in the 19th century. They participated in the first private motorway concession in France in 1970 and acquired the largest French toll road operating company when the government privatised their remaining toll road holdings in the early 2000s. Figure 1 shows their attractive portfolio of infrastructure development activities and concession agreements, the rump of which is airports and road, both of which are discussed in more depth below.

At the heart of VINCI’s success is the significant synergies generated from the combination of contracting and concessions:

- Having concessions generates maintenance work for their contracting subsidiaries and having engineering, design and project management skills gives them access to green- and yellowfields concessions, where they can add value without solely having to compete on cost of capital.

- The combination of more cyclical, low-capital intensity contracting with very stable, long duration, capital intensive concessions ensures a better risk-adjusted return and better long-term decision making. Both short-term cycles in contracting and the long-term investment cycles required for concessions can be absorbed without panicking or changing strategy.

- Contracting businesses normally run with large amounts of cash (due to prepayments or to back guarantees) and concession businesses operate with high gearing. The ability to deploy contracting cash into concessions allows them to be conservatively geared at a group level, while maintaining divisional efficiency. Due to the diversity of cash flows and low gearing, funding costs at group level is very low.

VINCI’s toll road assets consist of a 4 400km network of mainly intercity roads in France. This represents over half of French road concessions – in a country where the majority (76%) of highways are tolled. VINCI’s roads carry daily commuters, intercity business and leisure trips (also tourists) and freight. Their network links Paris, Spain and Italy, with very few alternative toll-free options. This is a key transport network for both the French and European economy.

The defining feature of these concessions is the high visibility of above inflationary cash flow growth. They have legally protected inflationary tariff increases, low variability due to massive margins and tailwinds from declining capital intensity and interest rates. The one variable less in their control is traffic, which has grown steadily over the long term. Traffic has only declined twice in the last 50 years and revenue hasn’t declined prior to 2020, and has already moved above pre-pandemic levels.

The framework for the concession agreements has been in place since 1956 and contains various protections for the concessionaire, including protection against changes in tax. These have been tested a few times in court and they have always held up. VINCI will operate these concessions until they revert to the state in the 2030s.

VINCI also owns 53 airports in 12 countries across the world, with the most significant being Portugal (10 airports), 50% of Gatwick in the UK, and a 40% stake in three Japanese airports. They are the second largest global airport operator.

Each airport and country have slightly different regulatory models. VINCI’s assets are mostly on the lighter end of the regulatory scale, and they have benefited from growing traffic and retail sales at their airports as well as tight cost control.

The attraction of airports relative to other concession assets are the long concession periods and historically fast growth, with air traffic expanding at roughly two times global GDP. Countering this are more volatile traffic growth and greater capital intensity. Despite the large impact of pandemic travel restrictions (VINCI airport made operating losses in both 2020 and 2021), the lasting impact of the crisis will be greater automation which has led to a permanently lower cost base and higher margins.

Even with no further concession investments, VINCI is likely to deliver a 10% shareholder return to the end of their current concessions. Given the visibility on price increases and growing air and road traffic, this return is reasonably certain with upside if inflation is higher than expected. We are confident that the combination of construction and concession expertise will lead to opportunities for further value creation.

Deregulated example: North American Rail

- A collection of stable local duopolies and monopolies between six different rail operators

- Competes against air and road freight but benefits relative to them at high carbon and oil prices

- Largely unregulated and free to set prices

- Will benefit from increasing volumes and further efficiencies

- Earnings are likely to endure for a very long time

The US freight rail system is made up of six companies, with pairs covering various regions (Figure 2). Union Pacific and Burlington Northern Santa Fe (Berkshire Hathaway’s railroad) operate in the west of the US. CSX and Norfolk Southern operate in the east, and Canadian National and Canadian Pacific operate from Canada into the US. Each pair forms a rational duopoly, and on some routes, the rails operate as monopolies.

The American rail system was largely developed by private companies, but after 1887 their pricing structures became strictly regulated by the Interstate Commerce Commission. As a result of the development of interstate highway and more efficient air travel, many railroad companies were driven out of business after the Second World War.

The fortunes of the industry were revived by the ratification of the Staggers Act of 1980, which largely removed price regulation and freed up railroads to negotiate with customers individually. This benefited both operators and users, and saw costs and prices halve over a 10-year period and the railroads reverse their market share losses against trucks.

Air, road and rail freight each have their own strengths and niches. Railways dominate long-distance bulk transport; trucking is much more flexible and cheaper over shorter distances; and airfreight dominates time-sensitive, high-value-to-weight freight. Rail operators benefit against their competitors when they become more efficient, flexible, and relatively cheaper; we believe all of these favour rail at the moment.

The rail companies are in various stages of implementing a process called precision-scheduled railroading (PSR), pioneered by Hunter Harrison at Canadian National, and which he perfected at both Canadian Pacific and CSX. PSR emphasises creating and executing an efficient rail schedule and continuously driving improvements to operating costs, car velocity and service levels on the network. This creates more capacity on the network, lower costs, more flexibility and, hence, more demand. Due to PSR, CSX’s margins expanded from 29% to 41.6% between 2011 and 2019, with flat volumes.

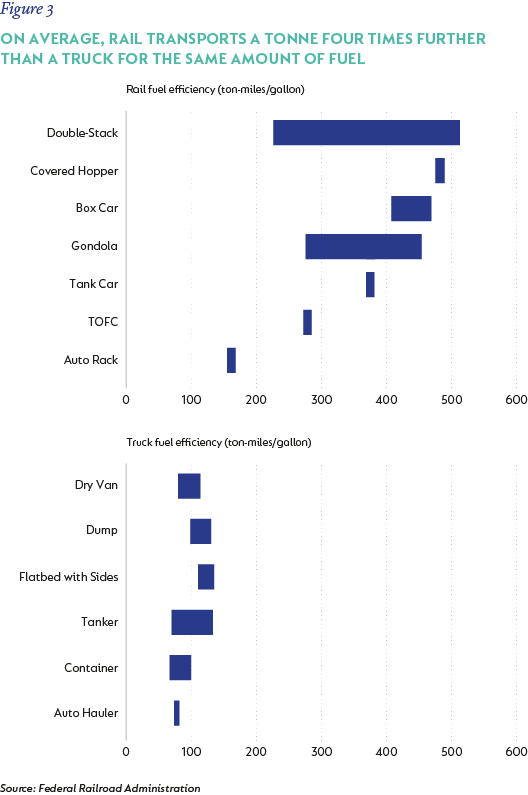

The relative cost position between different modes of transport is shifting. Fuel prices are a large part of variable cost for transport, but per tonne-mile rail’s fuel consumption is a quarter of road. Per dollar of revenue, trucks spend double on labour. We believe global energy prices and inflation will remain high and this will benefit railways relative to trucks. Companies are increasingly considering carbon costs when making supply-chain choices and rail has a far lower carbon intensity per mile than trucking or air freight.

Compared to the variable cost of trucking and air transport, a railway has a much greater portion of fixed costs. Greater usage drives lower unit costs in a virtuous circle. Rail volume is currently below normal. This is due to pandemic-related headwinds that are in the process of unwinding in the US (port operations slowed imports and exports, labour has been tight given Covid-19 challenges and reduced service levels) and Canada had a weak grain harvest in 2021 (grain is a higher margin category for the rails).

The rail companies trade on free cash flow yields of 4% to 6% and are likely to grow faster than the economy, as they take market share from other modes of transport. Compared to the average global business, we have much greater certainty that railway earnings will endure for many years.

Conclusion

Listed infrastructure assets offer great stability and certainty of earnings and are a key beneficiary of inflation. In an environment of rampant volatility and high inflation, these companies offer a counterbalance to more volatile holdings in a portfolio and we believe they will deliver superior risk-adjusted returns over time.

Henk Groenewald is an equity analyst and Humaira Surve is a portfolio manager at Coronation.