The Bank of Japan caught investors by surprise with an unexpected change to a core tenet of its monetary policy, sending shockwaves across the currency, bond and equity markets.

Traders described an adjustment to the longstanding yield curve control measures as potentially marking a “pivot” by the BoJ, the last of the world’s leading central banks to stick to an ultra-loose regime.

“We view this decision as a major surprise, as we had expected any widening of the tolerable band to be made under the new BoJ leadership from spring next year, similar to the market,” said Naohiko Baba, chief Japan economist at Goldman Sachs.

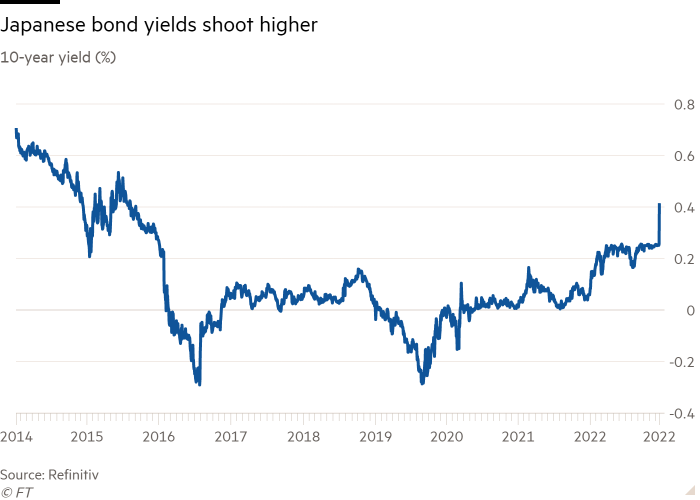

The yen jumped more than 4 per cent to about ¥131.2 against the US dollar in New York trading, while Japan’s Topix equity index fell 1.5 per cent. The 10-year Japanese government bond yield surged by its most in almost two decades, reaching a high of 0.47 per cent.

The BoJ’s move on Tuesday also ricocheted across other big markets: the US 10-year Treasury yield rose 0.11 percentage points to 3.69 per cent, while the equivalent UK gilt yield increased by a similar margin to 3.6 per cent. Yields rise when prices fall.

BoJ governor Haruhiko Kuroda denied the latest adjustment amounted to a tightening of monetary policy, stressing that the central bank would not scrap its yield target.

Japan’s increasingly extreme outlier status has contributed to a huge fall in the yen this year as markets have priced in the differential with the rate-tightening US Federal Reserve.

The central bank said it would allow 10-year bond yields to fluctuate by plus or minus 0.5 percentage points of its target of zero, instead of the previous band of plus or minus 0.25 percentage points. It kept overnight interest rates at minus 0.1 per cent.

Kuroda had earlier said any tweak to the yield curve control policy would effectively amount to an interest rate increase. But on Tuesday, he said the adjustment was meant to address increased volatility in global financial markets and improve bond market functioning to “enhance the sustainability of monetary easing”.

“This measure is not a rate hike,” Kuroda said. “Adjusting the YCC does not signal the end of YCC or an exit strategy.”

Japan’s core inflation — which excludes volatile food prices — has exceeded the BoJ’s 2 per cent target for the seventh consecutive month, hitting a 40-year high of 3.6 per cent in October.

But Kuroda had long argued that any tightening would be premature without robust wage growth, which is why most economists had expected the BoJ to stay the course until he steps down in April. On Tuesday, the central bank maintained its outlook that inflation would slow down next year and warned of “extremely high uncertainties” for the economy.

“Maybe it’s an act of generosity by Kuroda to reduce the burden for the next BoJ governor, but it’s a dangerous move and market players feel duped,” said Masamichi Adachi, chief Japan economist at UBS. “US yields are falling now but if they start to rise again, the BoJ would once again face the risk of being pressured into raising rates.”

The BoJ’s efforts to defend its YCC targets have contributed to a sustained reduction in market liquidity and what some analysts have described as “dysfunction” in the Japanese government bonds market. The central bank now owns more than half of outstanding bonds, compared with 11.5 per cent when Kuroda became governor in March 2013.

Kyohei Morita, chief Japan economist at Nomura Securities, said the BoJ’s move was probably best seen as a policy tweak rather than a full pivot. “Probably the BoJ wants to contribute to reducing the negative side effects of the yield curve control policy,” he said, noting that the bank’s outsized ownership of the Japanese government bonds market meant that liquidity had evaporated.

“They want to reactivate that market, even at the price of yen appreciation,” Morita said.

Mansoor Mohi-uddin, chief economist at Bank of Singapore, said the BoJ’s move was significant because it signalled the central bank was considering a broader exit from YCC, adding it would be an important turning point for the yen.

“The BoJ decision to raise interest rates in December 1989 led to a major sea change in Japanese markets,” said Mohi-uddin. “Today’s officials will be keenly aware of that history. It amplifies the significance of their signal to the markets today.”

Benjamin Shatil, foreign exchange strategist at JPMorgan, said the BoJ’s move would lead the market to start pricing in further policy moves, even if none were actually forthcoming.