Dear friends,

In like a lion, out like a lamb? The Total Stock Market Index has risen 12% in the past three months, as has the S&P 500. Nvidia stock is up 76% in the same period while semiconductor stocks inched up … 48%.

The thermometer in Davenport today topped 76 degrees, just a bit warm for a late winter day. We heard that participants in the March 1st Polar Plunges at locations across the upper Midwest had to be treated for heat stroke.

We live in interesting times. The one thing likeliest to help us through them is the support we offer one another, and our joint optimism that we can make it work!

In this month’s Mutual Fund Observer

Investors seem mesmerized by the potential for stock options, and so-called Zero Day options in particular, to perform the feat that never has been (spoiler: and never will be) done before: magically deliver the stock market’s gains with little of its pains. Money is rushing in a torrent toward such investments. Our colleague Devesh Shah, who dead asleep knows more about options than any of the rest of us do wide awake, takes us on a tour of the options industry and its manifestation in funds and ETFs.

GMO releases monthly its seven-year asset class forecast. In the wake of The Great Distortion (2008-2023), their forecast has become a reliable contrarian indicator; their first shall be last and their last shall be first, so to speak. That masks the fact that their work was remarkably accurate up until the era of zero-to-negative real interest rates and unbounded Fed creativity in propping up financial markets. How many people remember the emergency intervention in the overnight repo markets in 2021, where the Fed provided trillions of liquidity when the financial sector refused to, much less the fact that the Fed continued providing over a trillion until November 2023? If interest rates and Fed behavior return to their pre-2008 “normal,” GMO’s projections might suddenly become surprisingly valuable. I examine the argument, share the latest projection, and suggest six strategies and twelve funds that might be worth looking at … soon.

Most active fund strategies would probably benefit from being teleported into active ETFs, which tend to have both structural cost and tax advantages and a major PR advantage. While they’re gaining in popularity, they remain a surprisingly small niche. Lynn Bolin goes behind the curtains to identify the best – in terms of performance and persistence – and discusses their integration into a portfolio.

Investors all love the idea of winning big, a single dramatic bet paying off Las Vegas style. (“If you’d invested $10,000 in Nvidia five years ago, you’d have $200,330 today!” Which misses the fact that you didn’t invest in Nvidia; you bought a cannabis ETF and Beyond Meat stock.) The impulse toward “next big thing” investing is captured in funds that specialize in investing in “disruptors.” For the benefit of those tempted, we look at the relative fortunes of two classes of funds: those claiming to be “disciplined” and those claiming to be “disruptive.”

The Shadow catches us up with industry news in Briefly Noted, but also highlights serious concerns around one news item. The assets in passive strategies have now surpassed active ones. The foolish response is a kneejerk: “Well, good! Passive is cheaper and better.” The more thoughtful response is “Hmm… passive works as a free rider on the efforts of active managers to maintain some market discipline. But what happens if there are too few active managers to maintain that discipline?”

Slippery when elevated

In the past six years, the market has crashed three times: down 20%(2018), 34% (2020) and 34% (2022). Despite that, by measures such as the Shiller CAPE, we remain in one of the three most expensive markets in the past 150 years. Doug Ramsey Chief Investment Officer & Portfolio Manager at Leuthold Management reminds us,

… elevated valuations make the stock market more “accident prone,” and recent years (while positive on a net basis) certainly illustrate this. Consider that the last 5-1/2 years have seen three “major declines” in the S&P 500 (and significantly deeper losses for other indexes), despite the economy having been in recession for just two months out of that entire span. (P/E Multiples Still Matter, 2/7/2024)

By his calculation, the 2022 bear market ended at valuations higher than the peak of almost any bull market before it.

All great organizations have one thing in common

Over 40 years, I’ve built a lot of high-functioning programs and have studied a lot more. One factor, more than any other, distinguishes programs on a sustained upward path from those swirling around the toilet.

The leadership in high-functioning programs isn’t threatened by the success of others; they’re secure in the knowledge of their own abilities enjoy challenges and look to hire people better than themselves.

The leadership in low-functioning programs dwells in existential terror; they strut around a lot while wrought with angst, they’re afraid of being shown up and look to hire people who don’t threaten them.

Academic departments of speech or communication are generally not seen as being among a university’s elite units. “Home to the football team and the cheer squad” is the stigma. And yet at Augustana, one wannabe kingmaker’s plaintive query was, “Why does everything here run through the communication department?” We provided more Deans of the College, associate deans, division heads, senate chairs, council presidents, and program initiatives than any other academic program. That reflected a single impulse: we were relentless in pursuing new hires who were way better than we were, and adamant that we would rather find a one-year patch than hire someone who didn’t excite us.

As the longest-serving member of the department, I’m also, almost by definition, its weakest link since I’ve only been willing to hire people better than me and then people better than the ones we’d just hired.

It’s scary and exhausting, humbling and infinitely worthwhile.

All of which came to mind as I read Warren Buffett’s encomium to Charles Munger. It speaks to a profound humility, and a joyful embrace of a challenging hire, on Mr. Buffett’s part. It occupies the opening page of Buffett’s annual letter to shareholders. I’d like to quote a chunk of it for you.

Charlie Munger died on November 28, just 33 days before his 100th birthday.

Though born and raised in Omaha, he spent 80% of his life domiciled elsewhere. Consequently, it was not until 1959 when he was 35 that I first met him.

In 1962, he decided that he should take up money management. Three years later he told me – correctly! – that I had made a dumb decision in buying control of Berkshire. But, he assured me, since I had already made the move, he would tell me how to correct my mistake.

In what I next relate, bear in mind that Charlie and his family did not have a dime invested in the small investing partnership that I was then managing and whose money I had used for the Berkshire purchase. Moreover, neither of us expected that Charlie would ever own a share of Berkshire stock.

Nevertheless, Charlie, in 1965, promptly advised me: “Warren, forget about ever buying another company like Berkshire. But now that you control Berkshire, add to it wonderful businesses purchased at fair prices and give up buying fair businesses at wonderful prices. In other words, abandon everything you learned from your hero, Ben Graham. It works but only when practiced at small scale.” With much backsliding I subsequently followed his instructions.

Many years later, Charlie became my partner in running Berkshire and, repeatedly, jerked me back to sanity when my old habits surfaced. Until his death, he continued in this role and together we, along with those who early on invested with us, ended up far better off than Charlie and I had ever dreamed possible.

In reality, Charlie was the “architect” of the present Berkshire, and I acted as the “general contractor” to carry out the day-by-day construction of his vision.

Charlie never sought to take credit for his role as creator but instead let me take the bows and receive the accolades. In a way his relationship with me was part older brother, part loving father. Even when he knew he was right, he gave me the reins, and when I blundered he never – never –reminded me of my mistake.

About halfway through his long letter, Mr. Buffett makes a passionate promise that I suspect few of the quazillionaires in his circle would echo:

I believe Berkshire can handle financial disasters of a magnitude beyond any heretofore experienced. This ability is one we will not relinquish. When economic upsets occur, as they will, Berkshire’s goal will be to function as an asset to the country – just as it was in a very minor way in 2008-9 – and to help extinguish the financial fire rather than to be among the many companies that, inadvertently or otherwise, ignited the conflagration.

Our goal is realistic. Berkshire’s strength comes from its Niagara of diverse earnings … We also operate with minimal requirements for cash, even if the country encounters a prolonged period of global economic weakness, fear and near paralysis.

Your company also holds a cash and U.S. Treasury bill position far in excess of what conventional wisdom deems necessary. During the 2008 panic, Berkshire generated cash from operations and did not rely in any manner on commercial paper, bank lines or debt markets. We did not predict the time of an economic paralysis but we were always prepared for one.

Extreme fiscal conservatism is a corporate pledge we make to those who have joined us in ownership of Berkshire. In most years – indeed in most decades – our caution will likely prove to be unneeded behavior – akin to an insurance policy on a fortress-like building thought to be fireproof. But Berkshire does not want to inflict permanent financial damage – quotational shrinkage for extended periods can’t be avoided – on Bertie or any of the individuals who have trusted us with their savings.

Berkshire is built to last.

We are richer for the work, and standards, of such people. Would that there be more of them.

Speaking of Berkshire Hathaway … wow.

Professor Emerita Ruth Gottesman just changed the lives of thousands. Dr. Gottesman donated a billion dollars to the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. The college is located in one of the most impoverished parts of the city and the state of New York. Her gift quadruples the size of the college’s endowment. The school immediately announced its decision to eliminate tuition for all students. A medical newsletter walked through the implications of the gift: “This gesture is set to liberate future physicians from the daunting average medical school debt of $202,453 in the U.S., allowing them to pursue their careers unencumbered by financial strain.”

Professor Emerita Ruth Gottesman just changed the lives of thousands. Dr. Gottesman donated a billion dollars to the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. The college is located in one of the most impoverished parts of the city and the state of New York. Her gift quadruples the size of the college’s endowment. The school immediately announced its decision to eliminate tuition for all students. A medical newsletter walked through the implications of the gift: “This gesture is set to liberate future physicians from the daunting average medical school debt of $202,453 in the U.S., allowing them to pursue their careers unencumbered by financial strain.”

It will also increase the likelihood that smart kids who could never otherwise consider med school – first-generation college students, the children of immigrants, and the impoverished among them – might become the sort of doctors who transform communities.

NPR described her gift as “one of the largest charitable donations to an educational institution in the United States and most likely the largest to a medical school.”

The driver of the gift was her husband’s investment in Berkshire Hathaway. David Gottesman founded First Manhattan Corporation (FMC, one of whose funds we profiled), was an early investor in Berkshire Hathaway, and a partner of Mr. Buffett’s on several projects. Mr. Gottesman is described by Fortune Magazine as “a friend of Buffett for six decades, and his early investments in Berkshire Hathaway Inc. gave him a net worth of almost $3 billion as of mid-2022, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index.”

A quick growl at the world’s stupidest charitable contribution

Giving money to Harvard’s endowment. It’s absolutely idiotic and irresponsible. Harvard’s endowment is over $53 billion. That’s bigger than the GDP of 120 nations (CBS, 12/23/2023) and it is piling up relentlessly. It translates to an endowment of over $2.1 million per student. At a 4% draw, that’s enough for Harvard to eliminate entirely the $80,000 a year it charges.

But that’s not the way Harvard manages its budget. In consequence, it opens itself up to blackmail from rich alumni who threaten to withhold additional billions if the university doesn’t align itself with their political preferences. (Which, by the way, they have every right and reason to do.)

If there’s a “charity case” less compelling than helping Harvard build toward its 54th billion, I haven’t seen it.

And if you want to make a difference, go support the schools that support bright kids who might not otherwise make it, whether that’s the Albert Einstein College of Medicine or your local community colleges.

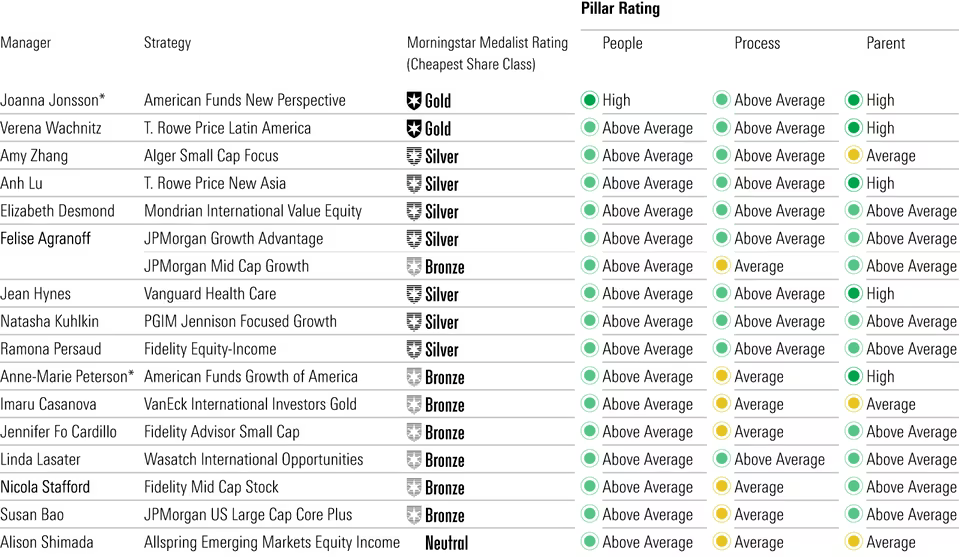

Morningstar recognizes top female fund managers

In celebration of International Women’s Day, Morningstar highlighted the work of 30 distinguished female fund managers. Traditionally, women have been badly underrepresented as both professional managers and individual investors (the industry assumed it just needed to confer with “the man of the house”), so we celebrate the effort.

Below is the list of managers in equity-oriented strategies. For the fixed-asset and allocation honorees, follow the link to Morningstar’s site.

The New Trillionaires

Knight Frank, a British real estate “consultancy” founded in 1896 has begun leaking to the media (the New York Times rather more than us) snippets from an upcoming report on intergenerational wealth transfer. Knight Frank estimates that a stunning $90 trillion is at play:

Over the next decade or so, a massive transfer of wealth and assets will occur as the silent generation and baby boomers hand over the reins to millennials. The shift will see US$90 trillion of assets move between generations in the US alone, making affluent millennials the richest generation in history.

One impact will come in how financial products are packaged and sold, but a more consequential one would flow from the very different levels of climate-related awareness and anxiety between younger and older investors.

The generational differences in investing strategies will vary, but climate change is just one example through which capital will be redirected. Looking solely at the top-line question on carbon emissions from our main Attitudes Survey of wealthy individuals and their advisors, millennials appear to have got the message when it comes to cutting consumption – 80% of male and 79% of female respondents say they are trying to shrink their carbon footprints. Male boomers take a different view, with just 59% trying to reduce their impact, well below their female peers (67%).

Those impending changes make the industry’s ongoing Green Flight more galling. Sustainability commitments that were too often the product of marketing calculations are crumbling under reactionary ire. The New York Times concludes, “Now, Wall Street has flip-flopped” (2/20/24) and they share a considerable list to support the conclusion. The most recent retreat was “JPMorgan, State Street, and Pimco have recently withdrawn from Climate Action 100+, a key international coalition aimed at pushing corporations toward greener practices.” (“Wall Street Firms Retreat from Climate Commitments Amid Growing Pressures,” One Green Planet, 2/2024). Their reasoning? The climate group “had gone too far.”

Young citizens, on the cusp of inheriting trillions, might reasonably ask, “What the very F does that even mean? They haven’t done anything!”

Two modest portfolio updates

In December, we profiled the newly launched GMO US Quality ETF (QLTY). In February, Chip added it to her portfolio.

In February, consistent with a plan that I discussed in my annual portfolio review, I increased my investments in both Leuthold Core and RiverPark Strategic Income. Irked as I am by the fact that the savings account at my bank pays 0.01% on all deposits – not to brag, but I pulled down well over $1.30 in interest last year – I’m in the process of shifting a chunk of it to David Sherman’s more conservative fund, RiverPark Short Term High Yield. Over the 13 years since its inception, David’s fund has the highest Sharpe ratio of any fund in existence: 2.52. To put this in perspective, that’s two and a half times greater than the next-best fund there is. The fund has averaged a 3.1% annual return; its lowest return in any 12 months was 0.6%. Its worst 12-month return is roughly 60X what Old National Bank has on offer, so …

Thanks, as always …

Thanks to the good folks at Gardey Financial and to Mark from Pennsylvania. (Hi, Mark! And thanks for the note. I, too, suspect that Lynn could probably muddle along pretty durn successfully without the help of a paid financial advisor. He’s really smart, but also smart enough to know his limits. I’m apt to leave full-time teaching after another year and I need to have a serious sit-down talk with one of the TIAA-CREF advisors out in Iowa City before I do. If I hear anything surprising, I’ll share.)

And, as ever, our Faithful Regulars: S & F Investment Advisors, Gregory, William, the other William, Stephen, Brian, David, and Doug.

As ever,