Dear friends,

It’s April. I spent much of the Easter weekend wearing a t-shirt out to work in the gardens. It was glorious. Today, the forecast is for hail. Tomorrow? Snow.

Next week? Oh, I don’t know … dragon fire?

And still, it behooves us to be grateful for what we have. The world’s most corrosive force is not greed. It’s envy, which is driven by the sense that what we have just isn’t enough, and bitterness that others have more. That’s a theme that Charlie Munger reflected on repeatedly: “I have conquered envy in my own life. I don’t envy anybody. I don’t give a damn what someone else has. But other people are driven crazy by it.” How crazy? Hmmm … think Biblically crazy: “If you want to talk about future implications, a lot of what I see now reminds me of Sodom and Gomorrah. You get activity feeding on itself, frenzies of envy and imitation” (2005).

It eventually even infected his sidekick, Warren Buffett: “There is no reason to look at the minuses in life. It would be crazy. We count our blessings.” (Yes, I know. Easier said if you’re worth $90 billion.)

The joyful secret to it is that the blessings don’t have to be large in order to be meaningful. Jancee Dunn, writing in the New York Times “Well” newsletter, reflected on her anxious day at the Times when she couldn’t figure out how to log in to the company’s network, was terrified that someone could overhear her fumbling on the phone, and so snuck off to meet one of the Wizards in the IT department (Chip assures me that she hires only wizards-in-training in IT.). Adnan The Wizard fixed her problem, commiserated, and shared a thought:

He told me to imagine a jar and suggested that I add a metaphorical penny to it every time I achieved something — even a task as small as finding my way back to my desk.

Over time, he said, you will fill up the jar. You will see that you are moving forward, even when you don’t feel that you are, he added.

I still think about that jar, especially when I’m having a rough time. I still deposit “pennies.” (“Feeling Overwhelmed? Try Tallying Your Tiny Wins,” NYT.com, 3/29/2024)

And so, in the face of hail and uncertainty, I celebrate my blessings: a loving family that I work to deserve, a meaningful calling and the trust of the families that make it possible, the sight of a bald eagle spiraling lazily above the tennis courts just beyond my window, time with all of you folks, and the signs that nature will give me another chance this year.

In this month’s Observer

One of my special blessings is the ability to work with folks whose understanding of issues is profound and complex and whose willingness to translate that understanding for your benefit seems boundless. Devesh, having spent a professional lifetime trading billions of dollars in options, completes his Options Trilogy for you this month. In March 2024, Devesh played out recent trends in options markets as he examined the almost manic rush into such funds. This month completes the trilogy with a deeper dive into the workings of options in 10 funds and a reflection on The Options Conundrum, including the question of whether you might not profit more with a Replicant Portfolio: an ultra-low-cost equity index and T-bills.

Lynn offers two pieces this month. First, he updates his profile of Fidelity New Millennium ETF (FMIL) by noting that … well, it’s gone. Fidelity launched a suite of active ETFs last month, one of which absorbed and transformed FMIL. Lynn shares his analysis of the suite on offer. Second, he analyzes the options of funds for long-term tax-efficient investing and comes up with two recommendations for you.

Finally, The Shadow brings us up to date on small victories for investors (umm, okay, a bit short there this month), the industry’s new strategies for Green Flight (rename the fund, redescribe the strategy, and, failing that, bail out), and we bid farewell to a near-record number of funds.

My contribution this month centers on this essay, where we’ll look at the market’s illusory calm, two investments you really want to explore, one you might pray to avoid, and a bunch of iterations on the same question: greed or envy, happiness or satisfaction?

I have two projects underway for you that attempt to help you think about strategies for dealing with unstable markets.

Infrastructure investing: as national governments fail to decelerate the rate of climate change, sub-national governments are increasingly planning massive infrastructure expenditures to mitigate some of the effects on human communities. Infrastructure expenses tend to operate in a rhythm independent of the stock market, which makes them useful for diversification. I’ve reached out to teams with three of the most promising funds. So far, I’ve got one “we’ll get back to you” and two dead silences. (Really, guys, take down the d**med “media contact” link if you’re incapable of even a polite “no thanks.”) I’ll continue those outreach efforts.

Quality investing: “quality at a reasonable price” reflects a remarkable market anomaly. The stocks of high-quality firms tend to be underpriced, solid in up-markets, and exceptional in volatile ones. The net effect is higher long-term returns with lower short-term volatility, which (theory says) shouldn’t happen. And it definitely shouldn’t happen consistently. But it does. An easy case can be made for the new GMO US Quality Equity ETF; as a matter of fact, we have made it, Chip was convinced to buy it, and it has easily outperformed its five-star, $10 billion sibling. We’ve been working with a Morningstar strategist who identified ten exceptional funds with an emphasis on quality investing. He shared commentary on each, and we’re still working out an understanding of what is directly quotable and attributable.

Rather than share half-complete projects, we’ve moved both to be featured stories in our May 2024 issue.

And why, you ask, worry about investments for unstable markets when the current market is eminently stable and rising? (Well, except that the Magnificent Seven have been reduced to the Fabulous Four.)

“Markets have a false sense of security”

The Wall Street Journal might be channeling their inner Devesh. They note that there’s been a flood of money into options-backed funds and ETFs, but the news is not all good. Jon Sindreu (3/8/2024) writes:

If you bought so-called structured products recently, you have plenty of company. But is precisely their popularity that could make them – and perhaps the entire stock market – riskier than they seem … The bargain often appeals to less-sophisticated investors who otherwise might not dabble in complex derivatives. For banks they bring in fat fees.

There follows a discussion of one class of derivatives called “autocallables.” At base, banks are the counterparties in the autocallable trade, so they have the incentive to hope for market stability, which, in part, is caused by their own need to buy “insurance” against their exposure to these options. Sindreu summarizes:

So autocallables look attractive because the stock market is calm, but the market is calm because people are buying so many autocallables. The feedback loop is reminiscent of the one created by funds that directly wagered against volatility back in 2017 and 2018. When a bout of selling broke the cycle, banks stopped hedging, volatility exploded and the market tanked.

His conclusion: you shouldn’t trust the Vix as a gauge of potential trouble. Quoting Jeffrey Yu of BNY Mellon, “Low volatility begets low volatility. Until something goes wrong.”

A week later, a second Journal writer echoed the warning:

The stock market is calmer than it has been in years. Some worry that a popular strategy is contributing to the tranquility.

Measures of market volatility have fallen to levels last seen in 2018 …

Investors are seeking protection from potential losses by pouring money into [covered-call ETFs] … assets in such funds has topped $67 billion, up from $7 billion at the end of 2020.

Their argument is that this sort of herd trade (in volatility ETFs) “blew up in spectacular fashion six years ago.” The options trade now exceeds stocks in value, with every covered-call position necessarily matched over an opposite position in “call overwrites.” The concern is that this is a complex, leveraged structure that might be catastrophically vulnerable to an external shock that causes a cascading rush to the exits. (See Charley Grant, “Popular bet weighs on volatility,” WSJ, 3/26/2024, B1. It’s online with a paywall and a slightly different title.)

Both are good pieces and remind us that the best time to patch the roof is before the rain begins. Our May features are aimed in that direction.

Good news, good guys, GoodHaven

Morningstar Magazine featured GoodHaven Fund, which we profiled in July 2023 (“The Rise of GoodHaven Fund“), in their March 2024 issue. Our quick summary: remarkable turnaround. Distinctive portfolio. Disciplined manager.

Morningstar Magazine featured GoodHaven Fund, which we profiled in July 2023 (“The Rise of GoodHaven Fund“), in their March 2024 issue. Our quick summary: remarkable turnaround. Distinctive portfolio. Disciplined manager.

We, and they, both note the manager’s principled decision to revamp his strategy in late 2020. The idea was to focus more on “special situations” only if they were demonstrably “special” and “quality at a reasonable price” strategy rather than focusing on purely statistical measures of cheapness.

It’s working.

Comparison of 3-Year Performance (April 2021 – March 2024)

| APR | Max drawdown | Downside deviation | Ulcer Index |

Sharpe Ratio |

Sortino Ratio |

Martin Ratio |

|

| GoodHaven | 17.3% | -17.8 | 10.1 | 6.6 | 0.86 | 1.44 | 2.19 |

| Multi-Cap Value peers | 8.6 | -18.0 | 10.8 | 6.4 | 0.35 | 0.55 | 1.06 |

| S&P 500 | 11.5 | -23.9 | 11.6 | 10.0 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 0.88 |

Source: MFO Premium fund screener and Lipper Global data feed

How to read that?

Returns: APR means the annual percentage return for the period

Risks: the maximum drawdown and downside deviation (called “bad deviation”) measure downside volatility for the period. In those cases, lower is better.

Risk-return balance: the Ulcer Index measures how far an investment falls and how long it takes to rebound. Smaller (as in “it gave me a smaller ulcer”) is better. The Sharpe, Sortino, and Martin ratios assess an investment’s returns against an increasingly high risk-management bar; that is, Martin is much more risk-averse than Sharpe. In each case, higher is better.

By those measures, GoodHaven has been a uniform and consistent winner. Morningstar frets that the fund “may not have broad appeal” because it doesn’t fit neatly into a box. So I guess if you care about boxes, you might turn to The Container Store. If you care more about performance, you might add GoodHaven to your due diligence list.

Microcap equity funds worth attention

I contributed, in partnership with Mark Gill, to a piece entitled “Microcap Funds” in the March 6, 2024 issue of Bottom Line. Bottom Line is a sort of cool “a bit of this and a bit of that” newsletter that covers personal topics from finance to nutrition and scholarship sources. I contribute occasionally. Mark and his editors assess reader interest in various topics, and one of the writers reaches out to talk with me. We talk. I share thoughts and data. He drafts, I revise.

The premise is that microcaps are profoundly undervalued relative to a bunch of measures and tend to perform exceptionally well when interest rates begin to fall since that often signals a period of economic acceleration. The MFO Premium screens identified about ten options, and Mark picked up on three.

With a bit more space, I would have urged him – and you – to investigate Pinnacle Value (PVFIX), which is a five-star fund managed by John E. Deysher. The fund embodies a low turnover, absolute value strategy that enables the manager to hold substantial cash when compelling opportunities are few.

With a bit more space, I would have urged him – and you – to investigate Pinnacle Value (PVFIX), which is a five-star fund managed by John E. Deysher. The fund embodies a low turnover, absolute value strategy that enables the manager to hold substantial cash when compelling opportunities are few.

Shallow observers will say, “he’s been in the bottom 10% of his peer group four times in the last ten years.” Those who look closer might note that John’s market cap is one-twentieth of his peer group’s, and he’s posted double-digit absolute returns in three of those four years. 2017 is the only actually bad year. In every period we track – whether 3/5/10 year windows or market cycles – Pinnacle’s Sharpe ratio ranges from “much higher” than its peers (50% higher since inception) to “ridiculously higher” (400% higher over the past three years). The fund’s standard deviation is half of the group’s.

One measure of the success of an absolute value strategy is the fund’s vast outperformance, measured in APR or annualized percentage rates, during the recent bear markets.

| 2007-09 GFC | 2020 Covid bear | 2022 bear | Full cycle – 2022 bear + subsequent bull | |

| Pinnacle Value | -24.8% | -23.3 | -7.7 | 12.5 |

| Small value average | -53.6 | -38.0 | -18.0 | 4.7 |

John manages about $34 million in assets, barely above where he was in 2015 when we profiled the fund. Our conclusion, then and now, is the same:

Mr. Deysher would prefer to give his investors the opportunity to earn prudent returns, sleep well at night, and, eventually, profit richly from the irrational behavior of the mass of investors. Over the past decade, he’s pulled that off better than any of his peers (2015).

“Irrational behavior of the mass of investors”? Where have I heard that before? Hmmm…

John is a laconic soul, so reading his 2023 Annual Report takes modestly less time than finishing your morning cup of coffee.

Trump in your portfolio

More correctly, Trump Media (DJT). Mr. Trump’s company, formerly Truth Social, is now publicly traded on the Nasdaq exchange. Over the week preceding April 1, 2024, it had a share price of between $43-73, giving it a somewhat volatile market cap. Its peak capitalization was $8 billion. It spent much of the last week of March at around $7 billion and began April at $5.5 billion. In terms of market cap, that’s in the neighborhoods of Etsy, Hasbro, Voya, or Invesco. About 5,000,000 shares a day have been trading hands. In 2023, the company had sales of $4 million (giving it a price/sales ratio of 1200) and lost $58 million (giving it a negative p/e ratio of minus 70). By comparison, the median annual sales of a McDonald’s location in 2020 was $2,908,000.

Because accounting is magical, the company reported a $50.5 million profit in 2022 on $1.5 million in revenue.

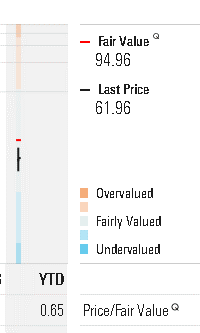

Because computers are magical, Morningstar’s algorithms have calculated a fair market value for DJT at $94.96 (as of April 1, 2024).

Not interested, you say?

You might not have a choice. The listing criteria for stocks in the Russell 3000 index are:

- Listing on a US stock exchange

- A share price above $1.00 on a ranking day at the end of May

- A market cap above $30 million

- A free market float of more than 5% (that is, more than 5% of the company’s total shares must be trading on the open market)

We have reached out to FTSE Russell, part of the London Stock Exchange Group, to understand their inclusion process but have not yet received a response.

Professional athletes and the economics of envy

There’s been a lamentable lot of commentary lately about National Football League players on $40 million/year contracts who deserve $60 million contracts. Their insistence on holding out for those last few millions reflects the fact that “they gotta take care of their families.”

Really?

The average American “takes care of their family” on $51,480 a year. (The Census reports household rather than individual incomes; the median there is $75,000 in 2022.) Loves them, hugs them, goes to their Little League games and piano recitals, cleans up their messes, and binds their wounds, psychic and physical. A 2014 study by the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce concluded, “Overall, the median lifetime earnings for all workers are $1.7 million,” with substantially higher payouts for folks with a BA ($2.3M), MA ($2.7M), PhD ($3.2M, and really I’ve got to find someone to sue over the gap between me and what I’m apparently owed) and MD/JD ($3.6M).

I am, as many of you know, a kid from Pittsburgh. In 1977, in the midst of a span in which the Steelers won four Super Bowls, future Hall of Fame players Joe Greene and Lynn Swann made $60,000 / year, approximately four-and-a-half times the average income for all Americans that year. Of course, they played for a guy, Art Rooney Sr., who walked to work every morning. In 2024 terms, a future Hall of Fame player making four and a half times the average income would be hauling in a cool $230,000 a year!

In reality, $40 million contracts reflect that you and I are much more interested in watching sports events than in participating – a parent-coach, sponsor, ref, athlete – in one. Our rapt attention to their fantasy world underwrites vast contracts and, occasionally, delusional behavior. You might not be more happy getting out to the (local) ballfield, but at the end of the day, you might find yourself rather more satisfied. Which cues …

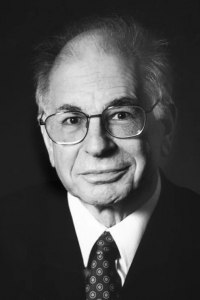

In memoriam … Daniel Kahneman (March 5, 1934 – March 27, 2024)

Dr. Kahneman passed away at the age of 90 after a life well and fully lived. He was recognized by The Economist as the world’s seventh most influential economist. That’s striking because (a) our fetish for meaningless rankings makes me smile, and (b) he wasn’t an economist.

Dr. Kahneman passed away at the age of 90 after a life well and fully lived. He was recognized by The Economist as the world’s seventh most influential economist. That’s striking because (a) our fetish for meaningless rankings makes me smile, and (b) he wasn’t an economist.

By “wasn’t an economist,” I mean “never even took a single Econ course in college.”

Kahneman was a professor of psychology whose work, along with Amos Tversky, laid the basis for the disciplines of behavioral economics and behavioral finance. His fundamental achievement was to categorize the consistent patterns of cognitive weirdness; others then found ways to make uncounted billions by exploiting those patterns. His book Thinking: Fast and Slow (2011) contains findings central to my teaching on propaganda and mass manipulation, but it’s also central to the curriculum of business programs across the country. Dr. Kahneman received the Nobel Prize in 2002, the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2013, two dozen honorary doctorates, and countless professional awards, including the Leontief Prize for contributions that “support just and sustainable societies.”

His less-known work on happiness and satisfaction aligns with my opening reflections in this letter. Kahneman and colleagues did rather a lot of work on the subject, only to discover that most people don’t want to be happy. They want to be satisfied. Happiness, he concluded, was the fleeting sensation of joy in a particular moment. It was evanescent. Satisfaction, he argued, “is a long-term feeling, built over time and based on achieving goals and building the kind of life you admire.”

Charlie Munger would, I think, understand. Stepping through the doorway of your million-dollar home and basking in the awe of your friends might make you happy. Living in an unassuming home and spending part of each week building shelters for others – as Lynn Bolin does and Jimmy Carter did – might be a surer road to satisfaction.

Thanks!

Thanks to Tom & Mes from TN, our old friend Gary in PA (I’ll share a bit more in May, but I’m very confident this will be a great year), and John of Honolulu.

To our faithful subscribers: Wilson, Gregory, William, William, Stephen, Brian, David, and Doug. The monthly reminders of your support mean a lot.

In the May Observer, I look forward to the case for infrastructure funds, quality investing, two fixed-income options, and general merriment. We hope to see you there!