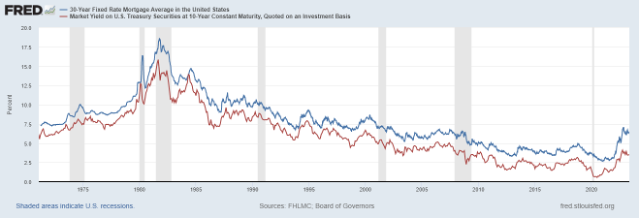

The massive inflation and double-digit mortgage rates of the 1970s and early 1980s seem to haunt the Federal Reserve, which wants to cool the economy and even provoke a job-loss recession to avoid that scenario.

But the latest Consumer Price Index inflation report shows how the fear of 1970s-style inflation is wildly overblown. Today’s numbers don’t look like the 1970s at all, when rent, wages, and oil shocks sent inflation running hotter than anything we have seen in recent modern-day history.

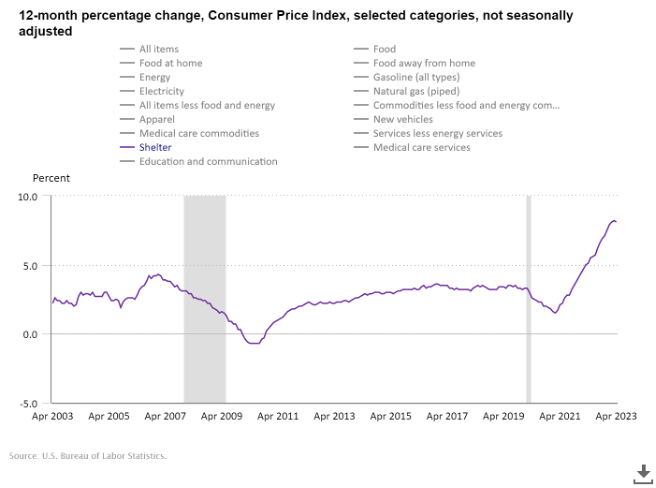

Shelter inflation

Shelter inflation had a mild lower print month to month in April. Since this data line is the most significant component of CPI — accounting for 44.4% of the index — the fact that this index is set to slow down over the next 12 months guarantees that we won’t see the boom in inflation that we saw in 1970s.

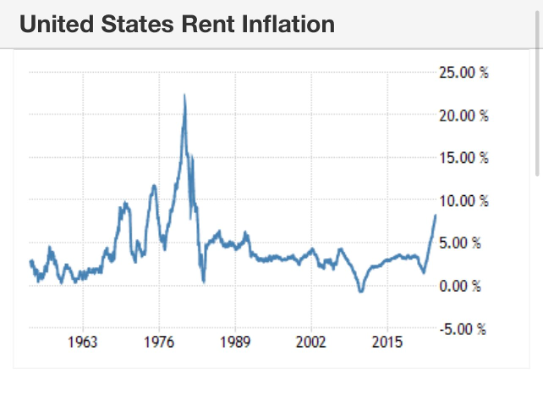

Rent inflation

We don’t need to worry about 1970s-style rent inflation. That kind of inflation couldn’t happen today because the shelter inflation growth rate has been cooling off already, and we have seen this in more real-time data.

Also, we have over 900,000 apartment units coming on line soon, and the best way to defeat inflation is with more supply. If you try to beat inflation by destroying demand, that is only a short-term fix. This is excellent news for mortgage rates, since falling rent inflation makes a better case for mortgage rates falling in the next year than rising.

In September on CNBC I talked about how the positive story for 2023 would be apparent by the start of the year: that the inflation growth rate was going to cool down, driven by shelter inflation. The inflation data lags, so I knew it would take time, but it happened.

Today, with massive rate hikes in the system and a banking crisis making credit tighter, the outlook for 1970s inflation is looking less and less. In reality, it never had a chance.

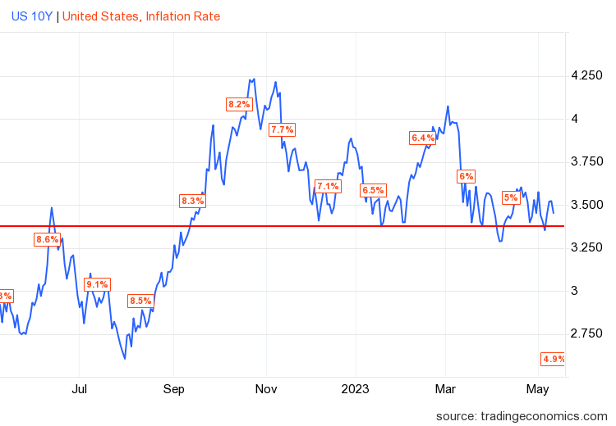

From the CPI report: The Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) rose 0.4 percent in April on a seasonally adjusted basis after increasing 0.1 percent in March, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Over the last 12 months, the all-items index rose 4.9 percent before seasonal adjustment.

How did mortgage rates react?

After the report, what did the 10-year yield do? It fell just as it should have, but it has still, held the Gandalf line in the sand — the area between 3.37%-3.42%. The chart below shows the 10-year yield versus the headline year-over-year inflation growth rate. As you can see, we have had much lower yields with hotter inflation data.

However, the 10-year yield looks like it has peaked unless the economy gets another wind and starts expanding much faster. On Oct. 27, I made the case for lower mortgage rates and bond yields in 2023. I believe the mega-bearish housing camp was counting on the 10-year yield getting toward 5.25%, and with bad spreads, that would get mortgage rates to 8%-10%.

My 2023 forecast for the 10-year yield and mortgage rates had one clear view, the 10-year yield should be between 3.21%-4.25 as long as the economy stayed firm. Staying firm means the labor market doesn’t break and jobless claims, people filing for unemployment benefits, stays under 323,000 on a four-week moving average. I have been more focused on the labor market this year than the inflation growth rate because I believe the market knew inflation was falling.

Of course, the banking crisis has added a new variable to the economic picture this year. However, even with that, the labor market, while getting softer, hasn’t broken yet. Mortgage rates did fall Wednesday to 6.57%, and that’s still higher than they should be because spreads between the 10-year yield and the 30-year mortgage rates are still historically high. If we had regular spreads today, mortgage rates would be roughly around 5.25%

Can you all imagine the housing market if mortgage rates were at 5.25% today? The Fed, which has said it wants a housing reset, would completely lose it. Under that reset, it’s older Americans who can buy homes, not younger Americans looking to start their life. This is one reason you haven’t heard a whisper from the Fed about helping the housing market during this time.

Labor market cooling

The labor market has been cooling recently, as job openings have fallen nearly 2.5 million from the peak in 2022. The Fed doesn’t fear a job-loss recess, and in fact their unemployment rate forecast for 2023 calls for one. They think they have a cover until job openings fall a lot more.

It looks to me that they will be more comfortable with job openings getting back to 7 million, which was where we were before COVID-19 hit us. I wrote about the recent jobs report and broke down a lot of labor data lines that matter to my 10-year yield mortgage rate forecast.

While the labor market is cooling, it hasn’t broken yet. If we had the 1970s inflation story, then the mortgage rates and bond yields could rise during a recession as they did back then. However, as we can see, the bond market never bit on the 1970’s inflation premise. Remember, these two loves have been slow dancing since 1971, and they never stop. Sometimes they’re closer to each other, and sometimes they’re farther apart. However, they are always together.

Overall, the CPI report didn’t have too many surprises, even though the headline number was lower than some anticipated. With the Federal Reserve, they’re looking at inflation without the shelter component because that data line lags and service inflation has been firm lately.

However, the story is set in stone: the Fed wants its recession because it will be a badge of honor for them when they pass off into the afterlife, as Paul Volcker has. They chose to hike rates more even though they knew credit was getting tighter and the banking crisis might help them hit their inflation target.

So, the reality is, what does the Fed do when the labor market breaks, with headline inflation looking like this? We are seeing the growth rate relax, and now the most significant variable in CPI will have a 12-month cooling-down tour.

This is why tracking weekly housing data will be more critical than ever this year. I don’t just track housing data, my primary job is to track economic cycles first and housing is a secondary data line. With all the drama we have going on in 2023, the rest of the year will get exciting week to week.