College professors are, quintessentially, learning machines. Give us 15 minutes of peace, and we’ll sink happily into piles of data, stacks of books, beckoning journal articles, or quiet processing.

And the reality of the matter is that almost no one gives anyone 15 minutes of peace these days.

Why 15 minutes? Read Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience (2008). Flow is a state of complete immersion in a project, and it seems to take us 15 minutes or so to get in the flow. Every “do you have just a minute?” kicks us back out and costs us another 15 minutes to get back.

Augustana’s January Term is, in that sense, a godsend. I teach one high-engagement course to 18 students. We meet five days a week for two 90-minute blocks each day. In exchange, the college demands nothing else of me: no retreats, no meetings, no committees, no social events, nothing. And so I had a chance to focus and to learn.

For what interest it holds, here are ten things I learned that you might benefit from.

The market value of The Magnificent Seven stocks exceeds the combined value of the Canadian, Japanese, and British stock markets

Those seven (bow, peasant) are worth more by a third than the entire Chinese stock market and more by 400% than all of the stocks in the Russell 2000 (Evie Liu, “Apple, Tesla, and the Rest of the Magnificent 7 Are Larger Than Entire Countries’ Stock Market,” Barron’s via MSN, 1/10/2024).

That inevitably calls to mind the reverse situation 35 years ago. Edward J. Epstein recalls the scene for us:

At its height, in 1989, real estate in Tokyo sold for as much as $139,000 a square foot—more than 350 times as much as choice property in Manhattan. Such valuation made the land under the Imperial Palace in Tokyo notionally worth more than all the real estate in California. The Japanese stock market, with some shares selling for a thousand times their earnings, similarly skyrocketed. Indeed, in 1989, the notional value of the stocks listed on the Tokyo exchange not only exceeded all the stocks in America but represented 44 percent of the value of all the equities in the world. (“What Was Lost (and Found) in Japan’s Lost Decade,” Vanity Fair, 2/17/2009)

Shortly thereafter, prices collapsed by 80%. The question for folks whose portfolios are dependent on seven stocks is, are we next?

2023 was the Year of The Magnificent Seven … and those other 4660 over in the corner.

Scott Opsal, director of research for the Leuthold Group, reports:

The Magnificent Seven’s remarkable performance defines the stock market in 2023. This basket of the seven largest companies in the S&P 500 index gained an average of 111% vs. an average gain of 9% for the other 493 companies. The combined impact of huge index weights and outsized performance made 2023 one of the most top-heavy markets in history. (“Fundamentally Magnificent,” 1/25/2024)

The question is, “Are those prices disconnected from reality?” Leuthold’s surprising answer was, “No, not really.”

One key feature of an investment bubble is the realization that asset prices are completely divorced from the fundamentals. From this perspective, the Magnificent Seven does not represent a bubble in the least. Rather, the group’s superiority is a testament to the investment results that come from identifying long-lasting trends that can power high earnings growth for a decade or more.

Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits, the investment classic written by Philip Fisher, is a must-read for every serious investor. Fisher’s premise is that investment success can be achieved by owning a handful of exceptional growth stocks for many years letting their compounding ability work in your favor. If you select these investments wisely, with the passage of time, the original purchase price becomes almost irrelevant. The Magnificent Seven stands as a proof of concept for this philosophy, and we wonder if the book’s publisher might be inclined to release a new edition with a bonus chapter on this extraordinary market story that has earned a place in stock market history.

Perhaps it’s time to consider the S&P 493?

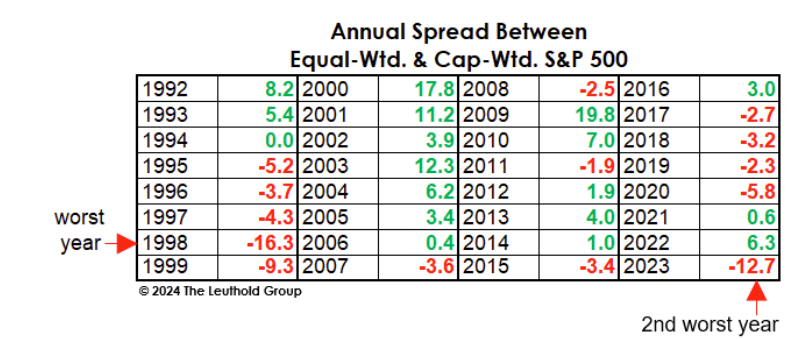

It’s the optimist’s play on passive investing. Standard & Poor’s has several versions of the S&P 500; the best known has the 500 (or s0) stocks weighted by their market capitalization so that the largest stocks – the Magnificent Seven, currently – almost entirely determine the index’s result. For short periods, that seems a magnificent strategy. More often, and over time, the better strategy is to invest in the same 500 stocks but weight your portfolio equally between all of them. That strategy imbues your portfolio with two biases: it favors slightly smaller stocks and somewhat cheaper sectors of the market.

The market-cap-weighted S&P 500 hit a record high in late January 2024. The equal-weighted S&P 500 strategy suffered an epic setback relative to the S&P 500 in 2023.

But, as Morningstar notes, the equal-weight S&P 500 provides better diversification and has actually outperformed the cap-weight version by about 1% annually over the course of the 21st century (Sarah Hansen, “Do you have the wrong index funds?” 1/19/2024). It also trades at more reasonable valuations. The WSJ’s Spencer Jakab notes:

The good news for long-term investors is that the stock market seems to have more of a concentration problem than a price or an earnings one. Mid-cap stocks sport a forward P/E ratio of 14.5 times, and small ones … are at just 14.1 times, according to Yardeni. That is a pretty middle-of-the-road valuation historically and is almost as cheap as that index has been relative to the large cap S&P 500 in more than two decades … Even most large stocks aren’t especially pricey: An equal weighted version of the S&P 500 …is close to its lowest ratio to the more mainstream index since the Global Financial Crisis. (“When Are Stocks No Longer a Good Value?” WSJ, 1/30/2024)

Interested investors might look at the behemoth Invesco S&P 500® Equal Weight ETF (RSP). In any case, it might be prudent to hedge a bit on your devotion to The Seven.

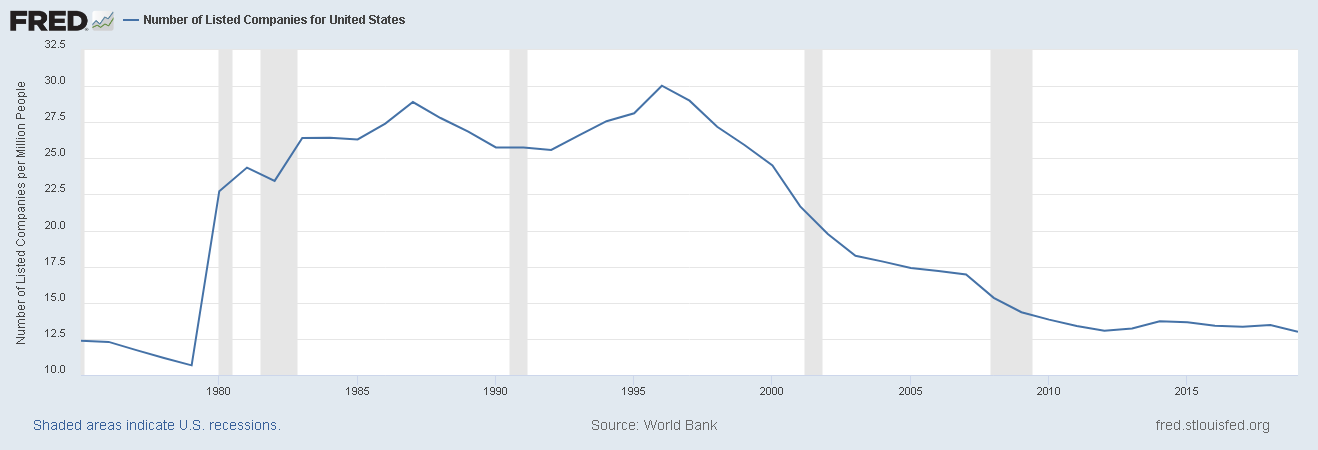

The US stock market is shrinking dramatically.

One inevitable consequence of vast corporate wealth, lax antitrust enforcement, and the incessant need for apparent growth to placate investors is the impulse of huge corporations to consume – merge with, acquire, buy up – smaller ones. Microsoft, for instance, has purchased 225 other corporations since 1986, including 14 valued at over $1 billion each (List of mergers and acquisitions by Microsoft, 2024).

The rate of consumption has consistently exceeded the rate of creation, and so the US stock market has narrowed. The Fed calculates the number of public corporations per million people to allow fair comparison across time.

The number of corporations per million of population was between 25-30 in the 1990s and is closer to 13 as of 2019 (inexplicably, that’s the most recent St. Louis Fed report and also the most recent for several other data sources. Statistica estimates that the number of NYSE stocks has fallen by about 500 since then, while the number of NASDAQ-listed ones remains roughly the same.

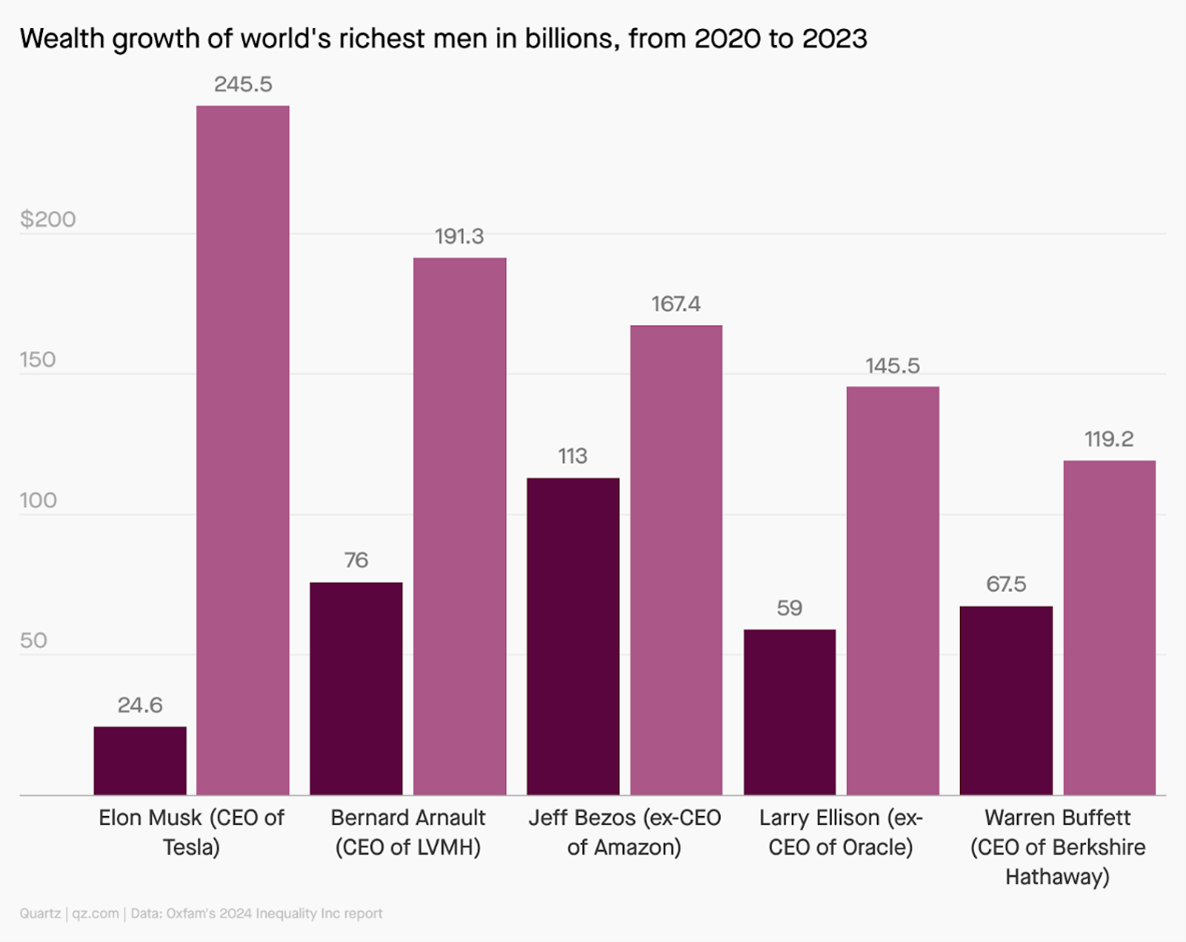

The world’s five richest men are accumulating wealth at the rate of $14,000,000 / hour.

The world’s richest men—Elon Musk, Bernard Arnault, Jeff Bezos, Larry Ellison, and Warren Buffett—have doubled their collective wealth to $870 billion since 2020. That’s a rate of $14 million an hour, with little sign of abatement, according to a new study from the UK-founded charity organization Oxfam.

ARK is destroying wealth almost as fast.

In a nice cautionary tale, Morningstar’s Amy Arnott tried to track down the landmines on which investors have most insistently trod. That is, she analyzed Morningstar’s vast trove of data to discover which individual funds and which fund families are lured the greatest number of investors to their doom. She ends up chronicling that antithesis of Tweedy, Browne’s famous What Has Worked in Investing.

The worst of the worst is ProShares UltraPro Short QQQ (SQQQ), a fund that allows investors to bet that the NASDAQ composite is going to fall today. By Arnott’s calculation, investors guessed wrongly: $8.5 billion worth of times. Fourteen of the 15 most destructive funds are ETFs, which are positioned as speculative vehicles as often as investment ones. And, as it turns out, speculation kills.

But SQQQ is a singular disaster. Arnott also takes a step back to ask what firms have pooled their efforts to produce the greatest collective act of wealth destruction. The answer is Cathie Wood’s ARK ETF Trust.

But SQQQ is a singular disaster. Arnott also takes a step back to ask what firms have pooled their efforts to produce the greatest collective act of wealth destruction. The answer is Cathie Wood’s ARK ETF Trust.

ARK, home of the flagship ARK Innovation ETF ARKK, tops the list for value destruction. After garnering huge asset flows in 2020 and 2021 (totaling an estimated $29.2 billion), its funds were decimated in the 2022 bear market, with losses ranging from 34.1% to 67.5% for the year. Many of its funds enjoyed a strong rebound in 2023, but that wasn’t enough to offset their previous losses. As a result, the ARK family wiped out an estimated $14.3 billion in shareholder value over the 10-year period—more than twice as much as the second-worst fund family on the list. ARK Innovation alone accounts for about $7.1 billion of value destruction over the trailing 10-year period. (Amy Arnott, “15 Funds that have destroyed the most wealth over the past decade”, Morningstar, 2/2024)

Given the number of warnings over seven years from both MFO and Morningstar, that shouldn’t be a surprise. And yet $16 billion remains entrusted to them. There’s a certain irony to the disconnect between the safety of the Ark and the effects of investing with ARK.

Speaking of wealth destruction, 95% of all NTFs have gone to zero.

A widely cited report by dappGambl (“your one-stop shop for unbiased reviews and analysis of cryptocurrency gambling platforms and Web 3.0 projects”)

Using data provided by NFT Scan, we have compiled a comprehensive analysis of over 73 thousand NFT collections … Of the 73,257 NFT collections we identified, an eye-watering 69,795 of them have a market cap of 0 Ether (ETH).

This statistic effectively means that 95% of people holding NFT collections are currently holding onto worthless investments. Having looked into those figures, we would estimate that 95% to include over 23 million people who’s (sic) investments are now worthless.

The estimate of 23 million NFT owners is inconsistent with most published estimates of eight million or so. We haven’t looked into dappGambl’s method for setting the higher figure. Regardless, major ruin.

NFTs are, at base, a stupid idea whose appeal was to casino-addled speculators. Nonetheless, NFT advocates foresee them rising, like a phoenix from its ashes, to become an $80 billion market in 2025. As we wrote in January 2023, “NFT advocates remain upbeat about the future of their product, which means they remain upbeat about the prospect of separating credulous investors from their wealth. I would decline the opportunity.”

Black Americans are becoming stock investors in record numbers.

Traditionally, Black Americans have participated in financial markets at far lower levels than have white Americans. There are a dozen good explanations for that decision, but the net effect is that those families did not have access to a powerful source of long-term wealth creation.

It’s good news that that’s changing. The Wall Street Journal reports:

Black Americans are the fastest-growing group of student buyers, with young Black investors fueling the surge. Nearly 40% of Black Americans owned stocks in 2022, up from just under a third in 2016 … nearly 70% of Black respondents under 40 years old were investing, compared to about 60% of white respondents in the same age group in 2022. (“Stock’s fastest-growing sector: Black investors,” 1/16/2024)

On the whole, Black investors are making more modest investments, are more likely to turn to friends and family, and are more likely to rely on social media sources for their financial guidance than white investors.

A note to young investors of all colors, faiths, and genders: Plan on getting rich slowly. I so wish that there was a reliable alternative to slow and steady gains, but there is not. Anyone who promises you a shortcut to wealth is, I suspect, mostly interested in acquiring your wealth for their gain.

If you’re 40 or younger, buy a super cheap, passive Total Stock Market or Total World Market index fund or ETF. Commit to automatically adding to it every month. If you’re, say, 40 to 60 years old, balance your investments with a strong tilt toward stocks. For the rest of us, balance your investments with a strong tilt toward bonds. A great guide for a prudent balance is the stock/bond/cash balance built into the T. Rowe Price Retirement funds, which are some of the best in the business.

50% of inflation was a corporate money grab.

Rural America is littered with angry billboards on the edges of farm fields and front yards, snarling at President Biden for somehow triggering the global price spasm of 2022. Setting aside the fact that the price jumps did not start in the US, were not unique to the US, and were not attributable to actions taken by the US (cf Markovitz and Marchant, “Why is inflation so high?” World Economic Forum, 2022), we now have a clearer sense of what influenced the magnitude of the spike.

Greed. (Duh.) From early on, we could see that the rise in the cost of corporate inputs (labor, energy, materials) was only half as great as the rise in consumer prices. A recent report by the public advocacy group Groundwork Collaborative attributes 53% of the price bump to the decision by corporate managers to use “the inflation crisis” as a cover to bump up earnings and cause, well, the inflation crisis.

Among the report’s key findings:

From April to September 2023, corporate profits drove 53% of inflation. Comparatively, over the 40 years prior to the pandemic, profits drove just 11% of price growth.

While prices for consumers have risen by 3.4% over the past year, input costs for producers have risen by just 1%. For many commodities and services, producers’ prices have actually decreased. Corporations have failed to pass these savings to consumers.

That’s bad news to consumers, especially those of us who eat … ummm, groceries which rose more than prices in other sectors and which disproportionately hits less affluent families despite efforts by the Biden administration to buffer the impact.

There is good news and bad for investors. The ability to transfer more money from consumers to corporations boosted corporate profits (the “earnings” in the price-to-earnings ratio) and made stock prices appear more reasonable. The inability to continue that particular act of legerdemain means that markets might appear increasingly overvalued.

Potatoes became popular in Europe as a tax minimization strategy

During the 17th and 18th centuries, wheat was the biggest crop in Europe. It was very visible, took up lots of space, and was easy to tax. As a way to avoid being taxed on their food, people started growing potatoes in their gardens. Above ground, it’s an unassuming plant that doesn’t draw much attention to itself. (Greg Byer, “19 surprising facts about the history of potatoes,” 2024)

Admittedly, more serious scholars attribute the potato’s rising popularity in the face of the peasants’ conservative reticence to “clever propaganda” (Rebecca Earl, “Promoting Potatoes in Eighteenth-Century Europe,” Eighteenth Century Studies, 2017). By some estimates, my Irish forebears ate 5.5 kilos of potatoes a day, with a single acre of land producing enough nourishment for an Irish-sized family (“How the humble potato changed the world,” BBC Magazine, 2020). Professor Earl even suggests that the whole of modern civilization is driven by the majestic spud (“How the humble potato fueled the rise of liberal capitalism,” The Conversation, n.d.)

Well, yes, I do read articles on the history of potatoes. But only after I finish ones on the global history of cheese.