Standing on a picket line in sub-zero temperatures outside St Mary’s hospital in west London on Thursday, members of the Royal College of Nursing were making history — but few took any pleasure in the fact.

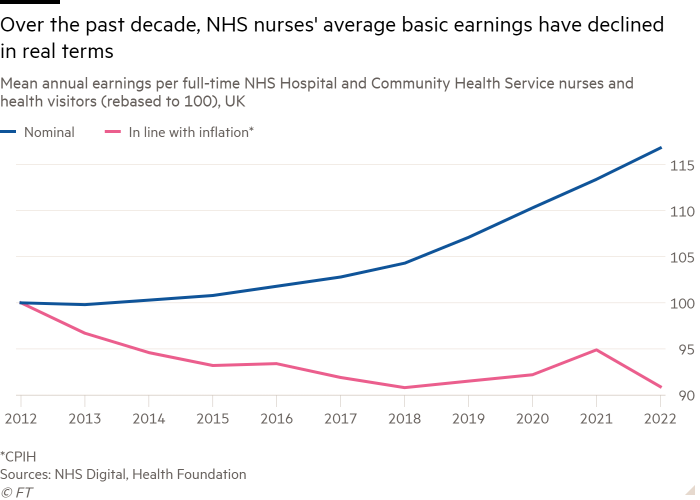

Reversing their union’s traditional opposition to strikes to hold the first stoppage in the RCN’s 106-year existence has been a psychological leap for many nurses. They argue that the progressive erosion of pay levels, which has in turn led to staff shortages, is putting patient safety at risk, but most are also deeply conflicted about swapping care for protest.

Among the cohort which had defied the chill to press home the union’s claim for a substantial above-inflation pay rise, the mood was less angry defiance than muted resolve.

Surrounded by colleagues holding placards saying ‘It’s time to pay nursing staff fairly’ and ‘Staff shortages cost lives’, Gerard Hamilton, a sexual and reproductive health nurse, said. “I don’t think anyone wants to be standing here.”

The RCN is asking for a pay rise of 5 per cent above retail price inflation, which was 14 per cent in November, but this has been rejected by the government.

“A demand of 19 per cent is not something we can realistically deliver on,” health minister Maria Caulfield told Sky News on Thursday. “We could’ve ignored the pay review bodies’ recommendation and gone for a much lower pay rise — we could go higher, but we have got to find that money from somewhere,” she said. “This isn’t government money, it’s taxpayers’ money.”

Although passing motorists — and ambulance drivers — honked their horns to signal support to Hamilton and his fellow strikers, he acknowledged that not all patients would understand why nurses have walked out.

“I think for some people they are still in this mindset that nursing is a vocation but we live in a very different society now. You’ll find there are many nurses who have more professional experience than many doctors and work in a similarly autonomous way, accepting full responsibility for everything they’re doing for patients,” he said.

Although nurses were lionised during the Covid emergency, Ruth Dawson, a nurse practitioner at St. Mary’s, felt there had since been no tangible recognition. Many of her colleagues were reduced to doing freelance shifts on top of their regular job to make ends meet. “Look at the whole impact on patient care of that, because we’re exhausted and when you’re exhausted it can put care at risk,” she warned.

Like Hamilton, she felt that while the profession had transformed over the decades, the pay and status had not kept pace. “I think we’re seen sometimes as [people who] hand things to doctors, when in fact we’re diagnosing and prescribing,” she said.

But the walkout had brought “really mixed emotions because we want to be doing our job, we want to be in [the hospital], but we’re at a point where there are no negotiations, [the government] can’t hear what we’re saying”.

At the other end of the country, Melissa Sing, 22, voiced similar concerns. She qualified as a nurse in September, after amassing £85,000 in debt doing a four-year integrated masters degree in nursing and social work.

“I just think if they don’t hear us, ultimately the NHS isn’t going to survive,” she said of the government, as she stood at the picket line outside the Royal Liverpool hospital. “There’s nurses leaving left, right and centre. People can’t afford child care, people are having to go to food banks,” she added.

Sing, who earns around £27,000 a year, was unsure exactly what would constitute an acceptable offer from ministers. “I just think there’s a way for them to give us a fair amount of pay that lines up with the cost of living, but they’re not even considering it. I don’t think we’re valued by the government.”

At nearby Alder Hey, one of Europe’s biggest children’s hospitals, 64-year-old clinical nurse specialist Adrian Williams said the strike was not only about money.

“It’s not just pay, it’s about the conditions and succession management,” he said. “I’m semi retired and came back three days [a week], but because they haven’t got people with my skills, I’m back four days and they’re trying to get me to do more.”

Newly qualified nurses are “much more knowledgeable than they ever were before and yet they’re in massive debt”, he added. “I started 30 years ago and was a paid student. The students coming through now are paying to be nurses.”

For Ellen Grogan, a 66-year-old nurse who is part of the St Mary’s strike committee, the walkout is also about patient safety. She retired last year after becoming deeply demoralised, and has returned to do freelance shifts. “We go to work and we’re short staffed on every shift so we are doing the work of two or three people. So obviously it’s not safe for patients,” she said.

She lashed out at what she called the “total moral treachery” of the government for not only failing to enter into pay negotiations but also for the way nurses were treated during the pandemic, when supplies of life-saving PPE were wholly inadequate.

She recalls going to a hardware shop and paying out of her own purse for goggles for her colleagues. Eventually, she said, she had “a real existential crisis . . . I felt that you couldn’t trust government, and that health service management had been pressured to collude with the government so you couldn’t trust them”.

She added that the RCN’s action, and wider campaigning for fair pay across the public sector, has “reinvigorated me and given me [a sense] that there is some hope to be had here”.