With interest rates now hovering around 5%, existing-home sales are down more than 14% from last year. Some potential buyers are sitting on the sidelines until rates or prices or both decline, while sellers are hoping the market picks up again so they can get a higher price.

But don’t count on rates falling to those pandemic lows. They were the result of extraordinary market manipulation from the Fed. And unless this becomes a regular feature of monetary policy, rates are not going back to what they used to be.

The real estate market has been on a wild ride. House prices, measured by the Case-Shiller index, increased 30% between March 2020 and December 2021, a steeper rise than the lead-up to end the housing bubble in 2008. This was in part because many people moved during the pandemic, but also because the 30-year mortgage rate was only 2.65% in spring of 2021.

The impact of the Fed’s interference may be felt for years. In the spring of 2020, the Fed was desperate to avoid economic collapse, so it reverted to its 2008 playbook. It cut rates to zero and brought back quantitative easing, buying long-dated government bonds and mortgage-backed securities (MBS). Most residential mortgages are securitized by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, and resold in what is known as an agency MBS.

In 2020, the mortgage-backed security market was in trouble, and the Fed was even more aggressive than it was in 2008. It effectively became the only ultimate buyer of these securities: Its holdings of agency MBS increased by $1.3 trillion between 2020 and 2022, while the market for agency mortgage-backed securities grew by $1.5 trillion. The Federal Reserve now holds more than 40% of the total outstanding amount of agency MBS, or nearly half the market.

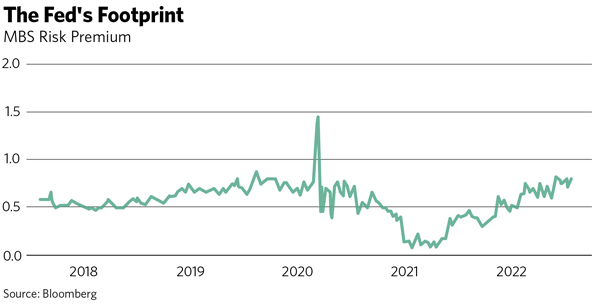

These actions were one big reason rates fell so low. Your mortgage rate is based on the 10-year bond rate, plus a premium for the extra risk involved. The size of that risk premium is largely determined in the MBS market, based on the liquidity and rate risk the investor takes on. The figure below shows the Bloomberg U.S. MBS index minus the yield on 10-year bonds.

The spread spiked at the start of the pandemic, but then as the Fed kept buying it fell to nearly zero, and the housing market raged. The spread started rising again in June once the end of QE was in sight, and it rose further when the Fed started to taper its purchases in the fall of 2021 before stopping in early 2022. The spread is now higher than it was before the pandemic.

Buying mortgage-backed securities may have made sense in spring 2020, but why the Fed did not start tapering for 18 months, even as the housing market was clearly overheating, was never explained. Whether quantitative easing actually helps the economy remains a divisive topic among economists. Fed economists insist it does help, while academic economists are more skeptical. But there is evidence that when the Fed buys mortgage-backed securities, it brings down MBS spreads and the mortgage rate.

Even though the Fed has ended QE, its role in fueling the screwy housing market may last for the next decade. The Fed would like to shrink the size of its MBS portfolio. So far it plans to do so by not reinvesting all the securities as mortgages are paid off.

But higher rates mean fewer people will refinance or move, so the mortgage portfolio won’t shrink as fast as the Fed anticipates. There are some whispers about the Fed selling some of its mortgage-backed securities. If that’s the case, Charles Schwab expects the MBS spread will grow even larger, and odds are so will your mortgage rates.

There will also be a hangover from the very low rates in 2020 and 2021. Like many people, I bought a home in the spring of 2021. Now between rising rates and a slower housing market, I am not sure I can ever afford to move. The housing market may be slower and less liquid for a long time.

The MBS market may be less liquid, too. Their buyers normally assume that a large number of mortgages won’t last 30 years because people move or refinance. But given that so many people got artificially cheap mortgages before rates went up means their behavior, and the duration of mortgage-backed securities, will be much less predictable. It will be a riskier asset that commands a larger spread.

The Fed has come under lots of criticism lately for being too late to raise rates in response to inflation. But another policy error could be that it kept buying so many mortgage-backed securities later in 2020 and most of 2021 when the housing market was on fire and rates kept dropping.

A 2.6% fixed rate on a 30-year risky asset never made much sense. It suggests something is off in the market, either through some manipulation or a mispricing of risk. The Fed created major distortions in a market where many Americans have most of their wealth, and the impact may be felt for decades.

Allison Schrager is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering economics. A senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, she is author of An Economist Walks Into a Brothel: And Other Unexpected Places to Understand Risk.