A few months after her wedding this year, Lilian Li moved from the south-western Chinese city of Chongqing to an apartment near Beijing’s financial district.

But while Chinese newly-weds typically see property ownership as an essential next step after marriage, Li and her husband are instead renting a two-bedroom apartment in the capital for Rmb13,000 ($1,821) per month.

To buy an identical apartment, Li and her family would need more than Rmb5mn just for the down payment — the equivalent of more than 30 years’ rent.

“My husband and I had a deep conversation about the life we want, and we reached an agreement not to buy,” said Li, 28. “We don’t want to owe our parents a massive down payment or to fall heavily into debt.”

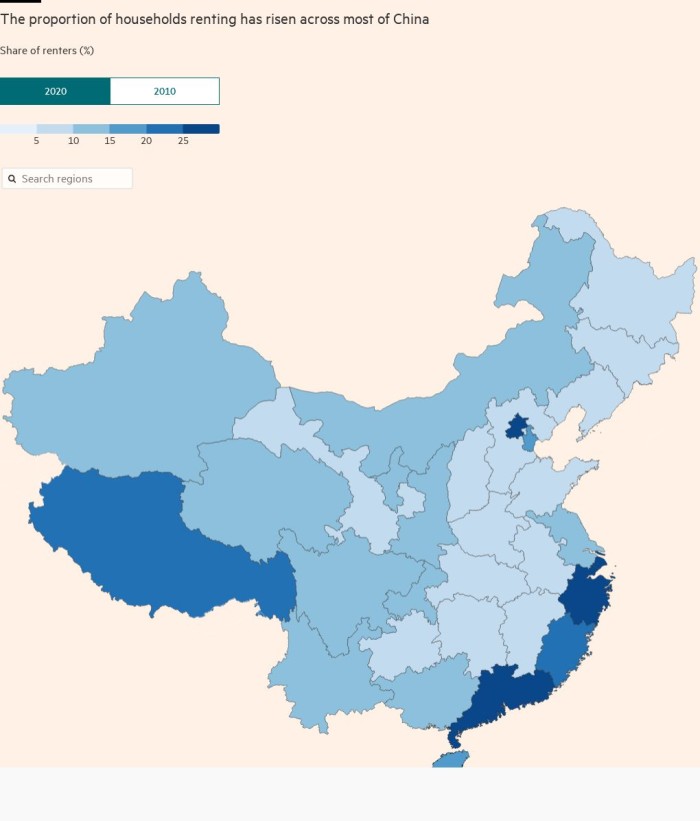

Increasing numbers of young Chinese, the main buyers of urban homes, are making the same decision — with potentially far-reaching implications for the nation’s troubled property market.

Affordability is a thorny issue for homebuyers in China, where average house prices have nearly doubled over the past decade. Rents have also increased, but by much less. The ratio of the cost to buy residential properties to their monthly rent was above 600 in major cities in June 2022, according to calculations by real estate data firm Zhuge Zhaofang. In 2007, the ratio was 400 or below.

A ratio of more than around 200 is considered a warning signal of a potential property price bubble, according to a report by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, a state think-tank.

In Beijing, the average apartment now costs about Rmb69,000 per square metre, according to real estate data provider creprice.cn.

First-time buyers typically rely on family support and debt to purchase a living space in big cities. But the woes of real estate developers such as Evergrande, which defaulted last year as a liquidity crisis gripped the property sector, have left many buyers with unfinished homes. That has prompted potential purchasers such as Li to question what has for decades been seen as China’s best household investment opportunity.

Chinese home sales by floor area in 100 cities were down about 20 per cent year on year in October, according to a survey by China Index Academy, a real estate research firm. While sales have not fallen as fast in prime areas of big cities, the pessimism across the market has dented confidence. And while new homes remain expensive, average prices across 70 cities were down 2.4 per cent in October from a year ago, the seventh consecutive month of decline, government data showed.

“With no wealth-creation effect, what’s the point of buying properties like crazy? Why not just rent?” said Victoria Zhan, a young banker who has postponed plans to buy an apartment in suburban Shanghai this year.

The research department of China International Capital Corporation forecast that the number of Chinese renting would grow by 200mn to reach 300mn by 2035.

The cooling enthusiasm for homebuying comes as the government moves to make more affordable rented housing available to young people as part of President Xi Jinping’s drive for “common prosperity”.

Authorities are pushing more government-subsidised rental homes on to the market and have rolled out “accommodative policies” for the sector including low-interest loans for developers of rental housing.

Qiqi Zhang, a Shanghai-based director at US private equity group Warburg Pincus, which first invested in rental property in China in 2013, said high house prices in major cities still put “a lot of pressure” on young people.

The government “really wants to promote rental housing to solve the accommodation needs of young people”, Zhang said.

In January, China’s housing ministry announced a target of 6.5mn units of affordable homes to be built in 40 cities over the five years to 2025, enough to house 13mn young people and new residents.

The government’s promotion of the rental housing market is increasingly intertwined with its support for property developers struggling to complete residential construction projects.

Financial regulators last month called for increased state-led conversion of unfinished homes to rental housing, and unveiled more sophisticated financial routes to help banks and investors buy out unfinished projects.

In response, the government of Kaifeng city in China’s central Henan province said it planned to buy more than 1,000 unfinished apartments next year from Evergrande and turn them into rental homes.

In the central city of Xi’an, seven banks including China Development Bank and China Construction Bank vowed to offer Rmb210bn credit lines to support rental housing projects.

CCB, the country’s second-largest bank by assets, said it had separately set up a Rmb30bn rental housing fund to buy out unfinished residential construction projects in more than 20 cities. Some projects were bought from developers at a 50 per cent discount to the price originally put on the homes, a banker familiar with the fund’s operation said.

In a research note, analysts at Morgan Stanley said state promotion of renting was in line with Xi’s 2015 call for housing to be “for living not for speculation”. But, they wrote, “the process will take time, and will for now mainly serve as downside support to the housing market”.

Li said renting rather than buying would save her and her husband money and so help them maintain their quality of life.

“We can buy an apartment in Chongqing when we are getting old and ready to retire,” she said. “Before that, I think we’ll keep renting in Beijing.”